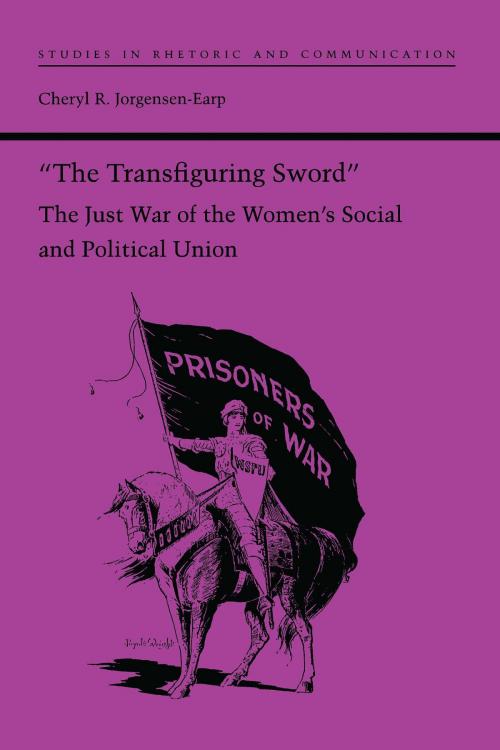

"The Transfiguring Sword"

The Just War of the Women's Social and Political Union

Nonfiction, Social & Cultural Studies, Political Science, Government, Elections, History, British| Author: | Cheryl R. Jorgensen-Earp | ISBN: | 9780817388416 |

| Publisher: | University of Alabama Press | Publication: | January 15, 2015 |

| Imprint: | University Alabama Press | Language: | English |

| Author: | Cheryl R. Jorgensen-Earp |

| ISBN: | 9780817388416 |

| Publisher: | University of Alabama Press |

| Publication: | January 15, 2015 |

| Imprint: | University Alabama Press |

| Language: | English |

Jorgensen-Earp provides a new understanding of the recurrent rhetorical need to employ conservative rhetoric in support of a radical cause.

The Women's Social and Political Union, the militant branch of the English women's suffrage movement, turned to arson, bombing, and widespread property destruction as a strategy to achieve suffrage for women. Because of its comparative rarity, terrorist violence by reform (as opposed to revolutionary) movements is underexplored, as is the discursive rhetoric that accompanies this violence. Largely because of the moral stance that drives such movements, the need to justify violence is greater for the reformist than for the revolutionary terrorist. The burden of rhetorical justification falls even more heavily on women utilizing violence, an option

generally perceived as open only to men.

The militant suffragettes justifed their turn to limited terrorism by arguing that their violence was part of a "just war." Appropriating the rhetoric of a just war in defense of reformist violence

allowed the suffragettes to exercise a traditional rhetorical vision for the sake of radical action. The concept of a just war allowed a spinning out of a fantasy of heroes, of a gallant band fighting against the odds. It challenged the imagination of the public to extend to women a heroic vision usually reserved for men and to accept the new expectations inherent in that vision. By incorporating the concept of a just war into their rhetoric, the WSPU leaders took the most conventional justification that Western tradition provides for the use of violence and adapted it to meet their unique circumstance as women using violence for political reform.

This study challenges the common view that the suffragettes' use of military metaphors, their vilification of the government, and their violent attacks on property were signs of hysteria and self-destruction. Instead, what emerges is a picture of a deliberate, if controversial, strategy of violence supported by a rhetorical defense of unusual power and consistency.

Jorgensen-Earp provides a new understanding of the recurrent rhetorical need to employ conservative rhetoric in support of a radical cause.

The Women's Social and Political Union, the militant branch of the English women's suffrage movement, turned to arson, bombing, and widespread property destruction as a strategy to achieve suffrage for women. Because of its comparative rarity, terrorist violence by reform (as opposed to revolutionary) movements is underexplored, as is the discursive rhetoric that accompanies this violence. Largely because of the moral stance that drives such movements, the need to justify violence is greater for the reformist than for the revolutionary terrorist. The burden of rhetorical justification falls even more heavily on women utilizing violence, an option

generally perceived as open only to men.

The militant suffragettes justifed their turn to limited terrorism by arguing that their violence was part of a "just war." Appropriating the rhetoric of a just war in defense of reformist violence

allowed the suffragettes to exercise a traditional rhetorical vision for the sake of radical action. The concept of a just war allowed a spinning out of a fantasy of heroes, of a gallant band fighting against the odds. It challenged the imagination of the public to extend to women a heroic vision usually reserved for men and to accept the new expectations inherent in that vision. By incorporating the concept of a just war into their rhetoric, the WSPU leaders took the most conventional justification that Western tradition provides for the use of violence and adapted it to meet their unique circumstance as women using violence for political reform.

This study challenges the common view that the suffragettes' use of military metaphors, their vilification of the government, and their violent attacks on property were signs of hysteria and self-destruction. Instead, what emerges is a picture of a deliberate, if controversial, strategy of violence supported by a rhetorical defense of unusual power and consistency.