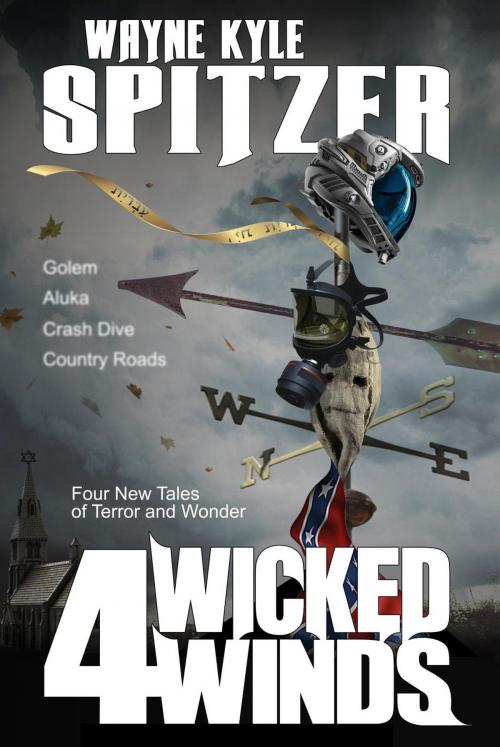

4 Wicked Winds: Four New Tales of Terror and Wonder

Science Fiction & Fantasy, High Tech, Fiction & Literature, Horror| Author: | Wayne Kyle Spitzer | ISBN: | 9781386563143 |

| Publisher: | Hobb's End Books | Publication: | March 28, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Wayne Kyle Spitzer |

| ISBN: | 9781386563143 |

| Publisher: | Hobb's End Books |

| Publication: | March 28, 2019 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

One wind is for a Jewish father, who calls up an unspeakable evil to avenge his son. Another is for an intersex hero caught up in a battle between men and women. Still another is for an astronaut thrown into black hole, where he sees the Face of God. Yet one more is for the hooded men who prowl the Kentucky night ...

By July, the body of a second Benton Boy had been discovered—my very own buddy, Colton.

They'd found him in a stone quarry about fifteen miles from town—the Eureka Tile Company, as I recall—his limbs broken and bent back on themselves ("like some discarded Raggedy Ann," wrote the local paper) and his head completely gone—which caused a real sensation amongst the townsfolk as each attempted to solve the riddle and at least one woman reported having seen it: "Just floating down the river, like a pale, blue ball."

But it wasn't until Rusty was killed that things reached a fever pitch, with Sheriff Donner under attack for failing to solve the case and neighbor turning against neighbor in a kind of collective paranoia—for by this point no one could be trusted, not in such a small town, and the killer or killers might be anyone, even your spouse or best friend.

It was against this backdrop that I was able to break from my lawn duties—which had exploded like gangbusters over the summer—long enough to visit the Mosses: which would have been the day before Independence Day, 1979. A Tuesday, as I recall. It's funny I should remember that. Aaron's mother was working in her vegetable garden—just bent over her radishes like an emaciated old crone—when I arrived, and didn't even look up when I asked if Aaron was around. "He's in his room—done sick with the flu. Best put on a mask before you go." She added: "You'll find some in the kitchen."

I think I just looked at her—at her curved spine and thin ankles, her tied up hair which had gone gray as a golem. Then I went into the house and made my way toward Aaron's room, passing his parents' quarters—upon which had been hung a 'Do Not Disturb' sign and a Star of David—on the way. I didn't bother fetching a mask; I'm not sure why—maybe it was because I was already convinced that whatever Aaron had, I had too. Maybe it was because I was already convinced that by participating in the ritual we'd somehow brought a curse upon us—a curse upon Benton—that it had never been just 'art' and that it could never be atoned for, not by Aaron or myself or Old Man Moss or anybody. That we'd blasphemed the Name of the Lord and would now have to pay, just as Jack had paid, just as Colton had paid. Just as Rusty had paid when they'd found him with his intestines wrapped around his throat and his eyeballs gouged out.

"Shut the door, please. Quickly," said Aaron as I stepped into his room—immediately noticing how dark it was, and that the windows had been completely blacked out (with the same sheets from the garage, I presumed). He added: "The light ... It—it's like it eats my eyes."

Christ—I know. But that's what he said: Like it ate his eyes.

I stumbled into a stool in the dark—it was right next to his bed—and sat down. Nor were the black sheets thick enough to completely choke the light, so that as I looked at him he began to manifest into something with an approximate shape: something I dare say was not entirely human—a thing thick and rounded and gray as the dead, like a huge misshapen rock, perhaps, or a mass of potter's clay, but with eyes. Then again it was dark enough so that I may only have imagined it—who's to say after forty years?

One wind is for a Jewish father, who calls up an unspeakable evil to avenge his son. Another is for an intersex hero caught up in a battle between men and women. Still another is for an astronaut thrown into black hole, where he sees the Face of God. Yet one more is for the hooded men who prowl the Kentucky night ...

By July, the body of a second Benton Boy had been discovered—my very own buddy, Colton.

They'd found him in a stone quarry about fifteen miles from town—the Eureka Tile Company, as I recall—his limbs broken and bent back on themselves ("like some discarded Raggedy Ann," wrote the local paper) and his head completely gone—which caused a real sensation amongst the townsfolk as each attempted to solve the riddle and at least one woman reported having seen it: "Just floating down the river, like a pale, blue ball."

But it wasn't until Rusty was killed that things reached a fever pitch, with Sheriff Donner under attack for failing to solve the case and neighbor turning against neighbor in a kind of collective paranoia—for by this point no one could be trusted, not in such a small town, and the killer or killers might be anyone, even your spouse or best friend.

It was against this backdrop that I was able to break from my lawn duties—which had exploded like gangbusters over the summer—long enough to visit the Mosses: which would have been the day before Independence Day, 1979. A Tuesday, as I recall. It's funny I should remember that. Aaron's mother was working in her vegetable garden—just bent over her radishes like an emaciated old crone—when I arrived, and didn't even look up when I asked if Aaron was around. "He's in his room—done sick with the flu. Best put on a mask before you go." She added: "You'll find some in the kitchen."

I think I just looked at her—at her curved spine and thin ankles, her tied up hair which had gone gray as a golem. Then I went into the house and made my way toward Aaron's room, passing his parents' quarters—upon which had been hung a 'Do Not Disturb' sign and a Star of David—on the way. I didn't bother fetching a mask; I'm not sure why—maybe it was because I was already convinced that whatever Aaron had, I had too. Maybe it was because I was already convinced that by participating in the ritual we'd somehow brought a curse upon us—a curse upon Benton—that it had never been just 'art' and that it could never be atoned for, not by Aaron or myself or Old Man Moss or anybody. That we'd blasphemed the Name of the Lord and would now have to pay, just as Jack had paid, just as Colton had paid. Just as Rusty had paid when they'd found him with his intestines wrapped around his throat and his eyeballs gouged out.

"Shut the door, please. Quickly," said Aaron as I stepped into his room—immediately noticing how dark it was, and that the windows had been completely blacked out (with the same sheets from the garage, I presumed). He added: "The light ... It—it's like it eats my eyes."

Christ—I know. But that's what he said: Like it ate his eyes.

I stumbled into a stool in the dark—it was right next to his bed—and sat down. Nor were the black sheets thick enough to completely choke the light, so that as I looked at him he began to manifest into something with an approximate shape: something I dare say was not entirely human—a thing thick and rounded and gray as the dead, like a huge misshapen rock, perhaps, or a mass of potter's clay, but with eyes. Then again it was dark enough so that I may only have imagined it—who's to say after forty years?