| Author: | Samuel Rawson Gardiner | ISBN: | 9780599460065 |

| Publisher: | Lighthouse Books for Translation Publishing | Publication: | May 19, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Lighthouse Books for Translation and Publishing | Language: | English |

| Author: | Samuel Rawson Gardiner |

| ISBN: | 9780599460065 |

| Publisher: | Lighthouse Books for Translation Publishing |

| Publication: | May 19, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Lighthouse Books for Translation and Publishing |

| Language: | English |

-

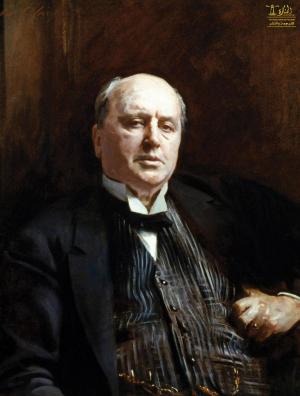

The New King. 1509.—Henry VIII. inherited the handsome face, the winning presence, and the love of pleasure which distinguished his mother's father, Edward IV., as well as the strong will of his own father, Henry VII. He could ride better than his grooms, and shoot better than the archers of his guard. Yet, though he had a ready smile and a ready jest for everyone, he knew how to preserve his dignity. Though he seemed to live for amusement alone, and allowed others to toil at the business of administration, he took care to keep his ministers under control. He was no mean judge of character, and the saying which rooted itself amongst his subjects, that 'King Henry knew a man when he saw him,' points to one of the chief secrets of his success. He was well aware that the great nobles were his only possible rivals, and that his main support was to be found in the country gentry and the townsmen. Partly because of his youth, and partly because the result of the political struggle had already been determined when he came to the throne, he thought less than his father had done of the importance of possessing stored up wealth by which armies might be equipped and maintained, and more of securing that popularity which at least for the purposes of internal government, made armies unnecessary. The first act of the new reign was to send Empson and Dudley to the Tower, and it was significant of Henry's policy that they were tried and executed, not on a charge of having extorted money illegally from subjects, but on a trumped up charge of conspiracy against the king. It was for the king to see that offences were not committed against the people, but the people must be taught that the most serious crimes were those committed against the king. Henry's next act was to marry Catharine. Though he was but nineteen, whilst his bride was twenty-five, the marriage was for many years a happy one.

-

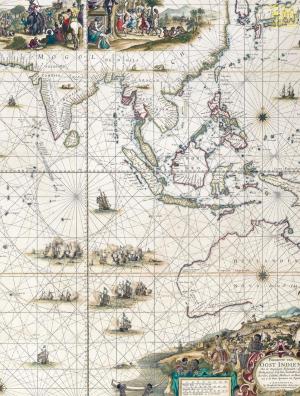

Continental Troubles. 1508-1511.—For some time Henry lived as though his only object in life was to squander his father's treasure in festivities. Before long, however, he bethought himself of aiming at distinction in war as well as in sport. Since Louis XII. had been king of France (see p. 354) there had been constant wars in Italy, where Louis was striving for the mastery with Ferdinand of Aragon. In 1508 the two rivals, Ferdinand and Louis, abandoning their hostility for a time, joined the Emperor Maximilian (see pp. 337, 348) and Pope Julius II. in the League of Cambrai, the object of which was to despoil the Republic of Venice. In 1511 Ferdinand allied himself with Julius II. and Venice in the Holy League, the object of which was to drive the French out of Italy. After a while the new league was joined by Maximilian, and every member of it was anxious that Henry should join it too.

-

The New King. 1509.—Henry VIII. inherited the handsome face, the winning presence, and the love of pleasure which distinguished his mother's father, Edward IV., as well as the strong will of his own father, Henry VII. He could ride better than his grooms, and shoot better than the archers of his guard. Yet, though he had a ready smile and a ready jest for everyone, he knew how to preserve his dignity. Though he seemed to live for amusement alone, and allowed others to toil at the business of administration, he took care to keep his ministers under control. He was no mean judge of character, and the saying which rooted itself amongst his subjects, that 'King Henry knew a man when he saw him,' points to one of the chief secrets of his success. He was well aware that the great nobles were his only possible rivals, and that his main support was to be found in the country gentry and the townsmen. Partly because of his youth, and partly because the result of the political struggle had already been determined when he came to the throne, he thought less than his father had done of the importance of possessing stored up wealth by which armies might be equipped and maintained, and more of securing that popularity which at least for the purposes of internal government, made armies unnecessary. The first act of the new reign was to send Empson and Dudley to the Tower, and it was significant of Henry's policy that they were tried and executed, not on a charge of having extorted money illegally from subjects, but on a trumped up charge of conspiracy against the king. It was for the king to see that offences were not committed against the people, but the people must be taught that the most serious crimes were those committed against the king. Henry's next act was to marry Catharine. Though he was but nineteen, whilst his bride was twenty-five, the marriage was for many years a happy one.

-

Continental Troubles. 1508-1511.—For some time Henry lived as though his only object in life was to squander his father's treasure in festivities. Before long, however, he bethought himself of aiming at distinction in war as well as in sport. Since Louis XII. had been king of France (see p. 354) there had been constant wars in Italy, where Louis was striving for the mastery with Ferdinand of Aragon. In 1508 the two rivals, Ferdinand and Louis, abandoning their hostility for a time, joined the Emperor Maximilian (see pp. 337, 348) and Pope Julius II. in the League of Cambrai, the object of which was to despoil the Republic of Venice. In 1511 Ferdinand allied himself with Julius II. and Venice in the Holy League, the object of which was to drive the French out of Italy. After a while the new league was joined by Maximilian, and every member of it was anxious that Henry should join it too.