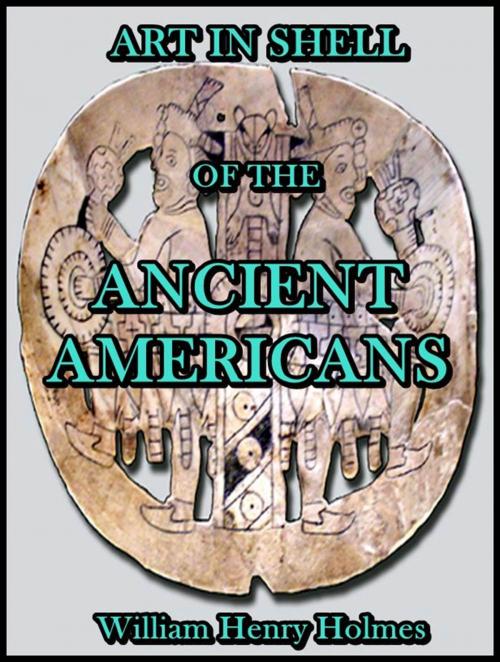

Art in Shell of the Ancient Americans

Kids, Beautiful and Interesting, Antiques and Collectibles, Natural World, Fossils, Nonfiction, History, Americas| Author: | William H. Holmes | ISBN: | 1230000231870 |

| Publisher: | SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION | Publication: | April 9, 2014 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | William H. Holmes |

| ISBN: | 1230000231870 |

| Publisher: | SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION |

| Publication: | April 9, 2014 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Art in Shell of the Ancient Americans

The student will find scattered throughout a wide range of archæologic literature frequent but casual mention of works of art in shell. Individual uses of shell have been dwelt upon at considerable length by a few authors, but up to this time no one has undertaken the task of bringing together in one view the works of primitive man in this material.

Works of ancient peoples in stone, clay, and bronze, in all countries, have been pretty thoroughly studied, described, and illustrated.

Stone would seem to have the widest range, as it is employed with almost equal readiness in all the arts.

Clay is widely used and takes a foremost place in works of utility and taste.

Metals are too intractable to be readily employed by primitive peoples, and until a high grade of culture is attained are but little used.

Animal substances of compact character, such as bone, horn, ivory, and shell, are also restricted in their use, and the more destructible substances, both animal and vegetable, however extensively employed, have comparatively little archæologic importance.

All materials, however, are made subservient to man and in one way or another become the agents of culture; under the magic influence of his genius they are moulded into new forms which remain after his disappearance as the only records of his existence.

Each material, in the form of convenient natural objects, is applied to such uses as it is by nature best fitted, and when artificial modifications are finally made, they follow the suggestions of nature, improvements being carried forward in lines harmonious with the initiatory steps of nature.

Had the materials placed at the disposal of primitive peoples been as uniform as are their wants and capacities, there would have been but little variation in the art products of the world; but the utilization of a particular material in the natural state gives a strong bias to artificial products, and its forms and functions impress themselves upon art products in other materials. Thus unusual resources engender unique arts and unique cultures. Such a result, I apprehend, has in a measure been achieved in North America.

Art in Shell of the Ancient Americans

The student will find scattered throughout a wide range of archæologic literature frequent but casual mention of works of art in shell. Individual uses of shell have been dwelt upon at considerable length by a few authors, but up to this time no one has undertaken the task of bringing together in one view the works of primitive man in this material.

Works of ancient peoples in stone, clay, and bronze, in all countries, have been pretty thoroughly studied, described, and illustrated.

Stone would seem to have the widest range, as it is employed with almost equal readiness in all the arts.

Clay is widely used and takes a foremost place in works of utility and taste.

Metals are too intractable to be readily employed by primitive peoples, and until a high grade of culture is attained are but little used.

Animal substances of compact character, such as bone, horn, ivory, and shell, are also restricted in their use, and the more destructible substances, both animal and vegetable, however extensively employed, have comparatively little archæologic importance.

All materials, however, are made subservient to man and in one way or another become the agents of culture; under the magic influence of his genius they are moulded into new forms which remain after his disappearance as the only records of his existence.

Each material, in the form of convenient natural objects, is applied to such uses as it is by nature best fitted, and when artificial modifications are finally made, they follow the suggestions of nature, improvements being carried forward in lines harmonious with the initiatory steps of nature.

Had the materials placed at the disposal of primitive peoples been as uniform as are their wants and capacities, there would have been but little variation in the art products of the world; but the utilization of a particular material in the natural state gives a strong bias to artificial products, and its forms and functions impress themselves upon art products in other materials. Thus unusual resources engender unique arts and unique cultures. Such a result, I apprehend, has in a measure been achieved in North America.