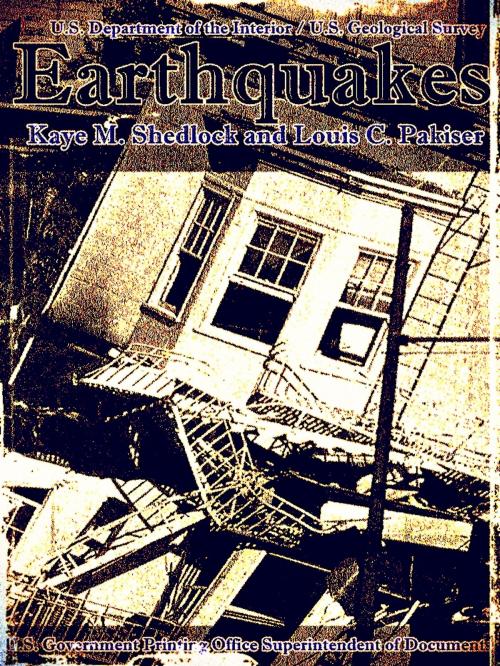

Earthquakes (Illustrations)

Nonfiction, Science & Nature, Nature, Environment, Earthquakes, Science, Earth Sciences, Geology, Natural Disasters| Author: | Louis Pakiser, Kaye M. Shedlock | ISBN: | 1230000284668 |

| Publisher: | U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents | Publication: | December 9, 2014 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Louis Pakiser, Kaye M. Shedlock |

| ISBN: | 1230000284668 |

| Publisher: | U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents |

| Publication: | December 9, 2014 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Example in this ebook

Earthquakes in History

The scientific study of earthquakes is comparatively new. Until the 18th century, few factual descriptions of earthquakes were recorded, and the natural cause of earthquakes was little understood. Those who did look for natural causes often reached conclusions that seem fanciful today; one popular theory was that earthquakes were caused by air rushing out of caverns deep in the Earth’s interior.

The earliest earthquake for which we have descriptive information occurred in China in 1177 B.C. The Chinese earthquake catalog describes several dozen large earthquakes in China during the next few thousand years. Earthquakes in Europe are mentioned as early as 580 B.C., but the earliest for which we have some descriptive information occurred in the mid-16th century. The earliest known earthquakes in the Americas were in Mexico in the late 14th century and in Peru in 1471, but descriptions of the effects were not well documented. By the 17th century, descriptions of the effects of earthquakes were being published around the world—although these accounts were often exaggerated or distorted.

The most widely felt earthquakes in the recorded history of North America were a series that occurred in 1811-12 near New Madrid, Mo. A great earthquake, whose magnitude is estimated to be about 8, occurred on the morning of December 16, 1811. Another great earthquake occurred on January 23, 1812, and a third, the strongest yet, on February 7, 1812. Aftershocks were nearly continuous between these great earthquakes and continued for months afterwards. These earthquakes were felt by people as far away as Boston and Denver. Because the 3 most intense effects were in a sparsely populated region, the destruction of human life and property was slight. If just one of these enormous earthquakes occurred in the same area today, millions of people and buildings and other structures worth billions of dollars would be affected.

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 was one of the most destructive in the recorded history of North America—the earthquake and the fire that followed killed nearly 700 people and left the city in ruins. The Alaska earthquake of March 27, 1964, was of greater magnitude than the San Francisco earthquake; it released perhaps twice as much energy and was felt over an area of almost 500,000 square miles. The ground motion near the epicenter was so violent that the tops of some trees were snapped off. One hundred and fourteen people (some as far away as California) died as a result of this earthquake, but loss of life and property would have been far greater had Alaska been more densely populated.

To be continue in this ebook

Example in this ebook

Earthquakes in History

The scientific study of earthquakes is comparatively new. Until the 18th century, few factual descriptions of earthquakes were recorded, and the natural cause of earthquakes was little understood. Those who did look for natural causes often reached conclusions that seem fanciful today; one popular theory was that earthquakes were caused by air rushing out of caverns deep in the Earth’s interior.

The earliest earthquake for which we have descriptive information occurred in China in 1177 B.C. The Chinese earthquake catalog describes several dozen large earthquakes in China during the next few thousand years. Earthquakes in Europe are mentioned as early as 580 B.C., but the earliest for which we have some descriptive information occurred in the mid-16th century. The earliest known earthquakes in the Americas were in Mexico in the late 14th century and in Peru in 1471, but descriptions of the effects were not well documented. By the 17th century, descriptions of the effects of earthquakes were being published around the world—although these accounts were often exaggerated or distorted.

The most widely felt earthquakes in the recorded history of North America were a series that occurred in 1811-12 near New Madrid, Mo. A great earthquake, whose magnitude is estimated to be about 8, occurred on the morning of December 16, 1811. Another great earthquake occurred on January 23, 1812, and a third, the strongest yet, on February 7, 1812. Aftershocks were nearly continuous between these great earthquakes and continued for months afterwards. These earthquakes were felt by people as far away as Boston and Denver. Because the 3 most intense effects were in a sparsely populated region, the destruction of human life and property was slight. If just one of these enormous earthquakes occurred in the same area today, millions of people and buildings and other structures worth billions of dollars would be affected.

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 was one of the most destructive in the recorded history of North America—the earthquake and the fire that followed killed nearly 700 people and left the city in ruins. The Alaska earthquake of March 27, 1964, was of greater magnitude than the San Francisco earthquake; it released perhaps twice as much energy and was felt over an area of almost 500,000 square miles. The ground motion near the epicenter was so violent that the tops of some trees were snapped off. One hundred and fourteen people (some as far away as California) died as a result of this earthquake, but loss of life and property would have been far greater had Alaska been more densely populated.

To be continue in this ebook