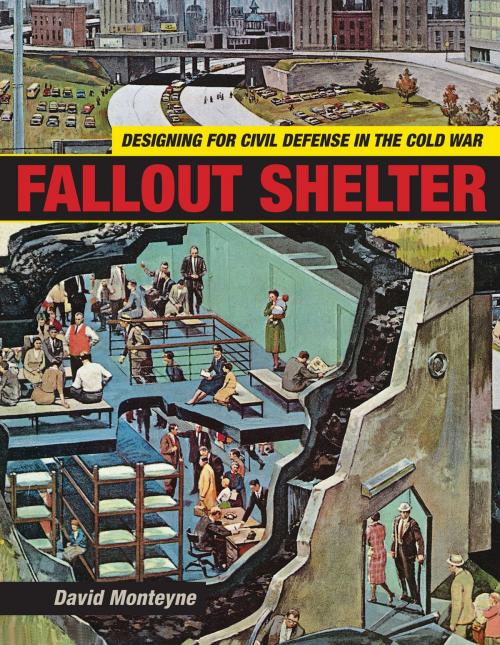

Fallout Shelter

Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War

Nonfiction, Art & Architecture, Architecture, History, Americas, United States, 20th Century| Author: | David Monteyne | ISBN: | 9781452925431 |

| Publisher: | University of Minnesota Press | Publication: | November 30, 2013 |

| Imprint: | Univ Of Minnesota Press | Language: | English |

| Author: | David Monteyne |

| ISBN: | 9781452925431 |

| Publisher: | University of Minnesota Press |

| Publication: | November 30, 2013 |

| Imprint: | Univ Of Minnesota Press |

| Language: | English |

In 1961, reacting to U.S. government plans to survey, design, and build fallout shelters, the president of the American Institute of Architects, Philip Will, told the organization’s members that “all practicing architects should prepare themselves to render this vital service to the nation and to their clients.” In an era of nuclear weapons, he argued, architectural expertise could “preserve us from decimation.”

In Fallout Shelter, David Monteyne traces the partnership that developed between architects and civil defense authorities during the 1950s and 1960s. Officials in the federal government tasked with protecting American citizens and communities in the event of a nuclear attack relied on architects and urban planners to demonstrate the importance and efficacy of both purpose-built and ad hoc fallout shelters. For architects who participated in this federal effort, their involvement in the national security apparatus granted them expert status in the Cold War. Neither the civil defense bureaucracy nor the architectural profession was monolithic, however, and Monteyne shows that architecture for civil defense was a contested and often inconsistent project, reflecting specific assumptions about race, gender, class, and power.

Despite official rhetoric, civil defense planning in the United States was, ultimately, a failure due to a lack of federal funding, contradictions and ambiguities in fallout shelter design, and growing resistance to its political and cultural implications. Yet the partnership between architecture and civil defense, Monteyne argues, helped guide professional design practice and influenced the perception and use of urban and suburban spaces. One result was a much-maligned bunker architecture, which was not so much a particular style as a philosophy of building and urbanism that shifted focus from nuclear annihilation to urban unrest.

In 1961, reacting to U.S. government plans to survey, design, and build fallout shelters, the president of the American Institute of Architects, Philip Will, told the organization’s members that “all practicing architects should prepare themselves to render this vital service to the nation and to their clients.” In an era of nuclear weapons, he argued, architectural expertise could “preserve us from decimation.”

In Fallout Shelter, David Monteyne traces the partnership that developed between architects and civil defense authorities during the 1950s and 1960s. Officials in the federal government tasked with protecting American citizens and communities in the event of a nuclear attack relied on architects and urban planners to demonstrate the importance and efficacy of both purpose-built and ad hoc fallout shelters. For architects who participated in this federal effort, their involvement in the national security apparatus granted them expert status in the Cold War. Neither the civil defense bureaucracy nor the architectural profession was monolithic, however, and Monteyne shows that architecture for civil defense was a contested and often inconsistent project, reflecting specific assumptions about race, gender, class, and power.

Despite official rhetoric, civil defense planning in the United States was, ultimately, a failure due to a lack of federal funding, contradictions and ambiguities in fallout shelter design, and growing resistance to its political and cultural implications. Yet the partnership between architecture and civil defense, Monteyne argues, helped guide professional design practice and influenced the perception and use of urban and suburban spaces. One result was a much-maligned bunker architecture, which was not so much a particular style as a philosophy of building and urbanism that shifted focus from nuclear annihilation to urban unrest.