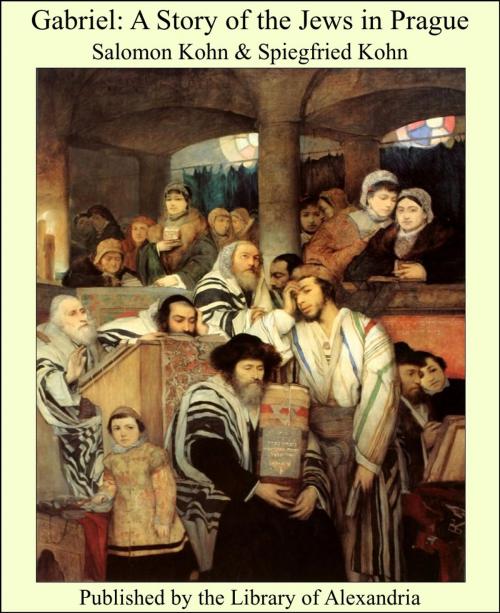

Gabriel: A Story of the Jews in Prague

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Salomon Kohn | ISBN: | 9781465538369 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Salomon Kohn |

| ISBN: | 9781465538369 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

It was the morning of a wintry autumnal day in the year 1620, when a young man stepped slowly and thoughtfully through the so-called Pinchas-Synagogue Gate into the Jews’ quarter in the city of Prague. A strange scene presented itself. The morning service was just over in the synagogues, and whilst numerous crowds were still streaming out of the houses of prayer, Others, mostly women with heavy bunches of keys in their hands, were already hurrying to the rag-market situated outside of the Ghetto. The shops too and stalls within the Ghetto were now opened, and even in the open street an activity never seen in the Other quarters of the city displayed itself. Here, for instance, dealers—in truth of the lowest class—were offering their wares consisting of pastry, wheat-bread, fruits, cheese, cabbage, boiled peas and more of such kind of stuff to the passers-by. Here and there too in spite of the early hour emerged some peripatetic cooks, in peaceful competition extolling loudly the products of their kitchen, bits of liver, eggs, meat and puddings, and whilst in one hand they held a tin plate, in the Other a two-pronged fork,—a very unnecessary article for most of their guests,—devoted their attention chiefly to the foreign students of the Talmud. To them also the greatest attention was paid by those cobblers who less wealthy than their colleagues in the so-called Golden St. offered their services to the students in open street, and most assiduously, while the owners were obliged to wait in the street or a neighbouring house, mended their shoes at a very moderate price, but, it must also be allowed, in a very inefficient manner. The young man who had just stepped into the Jew’s quarter, gazed earnestly and observantly at this busy stir, and did not seem to notice, that he himself had become an object of common attention. His appearance was however fully calculated to excite observation. His form was powerful and commanding; his dress that of a Talmud-student, cloak and cap. Out of his pale face shadowed by a dark beard, under heavy arching eyebrows there shone two black eyes of uncommon brilliance; raven locks fell in waves from his head; the fingers of a white sinewy hand, that held close the silken cloak, were covered with golden rings; his thick ruff was of spotless purity and smoothness.

It was the morning of a wintry autumnal day in the year 1620, when a young man stepped slowly and thoughtfully through the so-called Pinchas-Synagogue Gate into the Jews’ quarter in the city of Prague. A strange scene presented itself. The morning service was just over in the synagogues, and whilst numerous crowds were still streaming out of the houses of prayer, Others, mostly women with heavy bunches of keys in their hands, were already hurrying to the rag-market situated outside of the Ghetto. The shops too and stalls within the Ghetto were now opened, and even in the open street an activity never seen in the Other quarters of the city displayed itself. Here, for instance, dealers—in truth of the lowest class—were offering their wares consisting of pastry, wheat-bread, fruits, cheese, cabbage, boiled peas and more of such kind of stuff to the passers-by. Here and there too in spite of the early hour emerged some peripatetic cooks, in peaceful competition extolling loudly the products of their kitchen, bits of liver, eggs, meat and puddings, and whilst in one hand they held a tin plate, in the Other a two-pronged fork,—a very unnecessary article for most of their guests,—devoted their attention chiefly to the foreign students of the Talmud. To them also the greatest attention was paid by those cobblers who less wealthy than their colleagues in the so-called Golden St. offered their services to the students in open street, and most assiduously, while the owners were obliged to wait in the street or a neighbouring house, mended their shoes at a very moderate price, but, it must also be allowed, in a very inefficient manner. The young man who had just stepped into the Jew’s quarter, gazed earnestly and observantly at this busy stir, and did not seem to notice, that he himself had become an object of common attention. His appearance was however fully calculated to excite observation. His form was powerful and commanding; his dress that of a Talmud-student, cloak and cap. Out of his pale face shadowed by a dark beard, under heavy arching eyebrows there shone two black eyes of uncommon brilliance; raven locks fell in waves from his head; the fingers of a white sinewy hand, that held close the silken cloak, were covered with golden rings; his thick ruff was of spotless purity and smoothness.