| Author: | William B. Secrest | ISBN: | 9781618090683 |

| Publisher: | The Write Thought | Publication: | July 19, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | William B. Secrest |

| ISBN: | 9781618090683 |

| Publisher: | The Write Thought |

| Publication: | July 19, 2012 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

For many years one of the prime hardships on the western American frontier was the scarcity of women. Men could endure living a rough existence out in the open, fighting Indians and the elements, but the loneliness of life without women could become almost unendurable. Miners hacking out the wealth of the California Mother Lode treasured a scratched and bent tintype portrait of a woman as they would a solid gold nugget.

When a white woman came to the mines, anything could happen as the miners came from miles around just to get a glimpse of her and follow her around. In 1849 a woman advertised in a Marysville newspaper that she was looking for a husband and for the sum of $20,000, and a few other requirements, she would consider all comers. There can be little doubt that she had all the men she wanted to choose from. An enterprising miner got away with charging $5.00 a head to be a guest at his wedding and it was no surprise when he had standing room only for the late arrivals.

In the Gold Rush camp of Downieville, it is said that as the first woman to enter the area was seen ascending the trail, the miners streamed up the hill to meet her and picked up the mule, rider and all, carrying them both triumphantly into town. Whether the story is authentic or not, it is true to the spirit of the time. Women were venerated and cherished, not only because they were unprocurable, but because they represented the homes and the families that had been left behind. They represented a civilizing influence that all decent men everywhere yearned for when surrounded by primitive conditions.

It’s true there were a few harlots and gambling women in the mines and these did a flourishing business. The few moments spent with a prostitute were worth almost any price, not merely for the sexual gratification, but for the experience of just being near a woman. The gambling halls were filled to capacity with bearded and shaggy miners willing to lose a month’s wages just for the privilege of sitting opposite a woman monte dealer. To men without women, these moments were priceless and, generally speaking, the lowest of harlots was treated as respectfully as any pillar of the community.

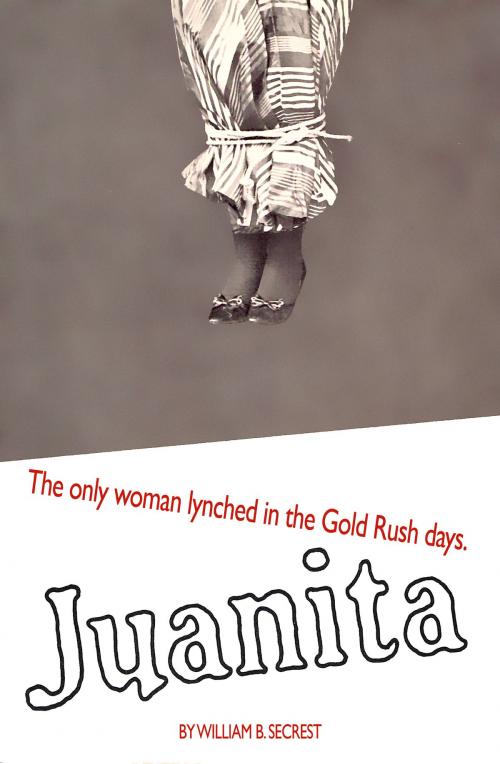

What was it, then, that went wrong that summer of 1851? For one day a frenzied mob disregarded an unwritten rule and committed a crime that horrified a whole state. Mob rule was the law in those early days, but there were bounds beyond which not even a mob would venture. And yet they did just once.

Using contemporary accounts, William B. Secrest (author of California Desperados and a dozen other titles) has chronicled the bizarre tale of Juanita, the only woman lynched in the California Gold Rush days.

For many years one of the prime hardships on the western American frontier was the scarcity of women. Men could endure living a rough existence out in the open, fighting Indians and the elements, but the loneliness of life without women could become almost unendurable. Miners hacking out the wealth of the California Mother Lode treasured a scratched and bent tintype portrait of a woman as they would a solid gold nugget.

When a white woman came to the mines, anything could happen as the miners came from miles around just to get a glimpse of her and follow her around. In 1849 a woman advertised in a Marysville newspaper that she was looking for a husband and for the sum of $20,000, and a few other requirements, she would consider all comers. There can be little doubt that she had all the men she wanted to choose from. An enterprising miner got away with charging $5.00 a head to be a guest at his wedding and it was no surprise when he had standing room only for the late arrivals.

In the Gold Rush camp of Downieville, it is said that as the first woman to enter the area was seen ascending the trail, the miners streamed up the hill to meet her and picked up the mule, rider and all, carrying them both triumphantly into town. Whether the story is authentic or not, it is true to the spirit of the time. Women were venerated and cherished, not only because they were unprocurable, but because they represented the homes and the families that had been left behind. They represented a civilizing influence that all decent men everywhere yearned for when surrounded by primitive conditions.

It’s true there were a few harlots and gambling women in the mines and these did a flourishing business. The few moments spent with a prostitute were worth almost any price, not merely for the sexual gratification, but for the experience of just being near a woman. The gambling halls were filled to capacity with bearded and shaggy miners willing to lose a month’s wages just for the privilege of sitting opposite a woman monte dealer. To men without women, these moments were priceless and, generally speaking, the lowest of harlots was treated as respectfully as any pillar of the community.

What was it, then, that went wrong that summer of 1851? For one day a frenzied mob disregarded an unwritten rule and committed a crime that horrified a whole state. Mob rule was the law in those early days, but there were bounds beyond which not even a mob would venture. And yet they did just once.

Using contemporary accounts, William B. Secrest (author of California Desperados and a dozen other titles) has chronicled the bizarre tale of Juanita, the only woman lynched in the California Gold Rush days.