Pictorial Composition and the Critical Judgment of Pictures

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Henry Rankin Poore | ISBN: | 9781465547880 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Henry Rankin Poore |

| ISBN: | 9781465547880 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

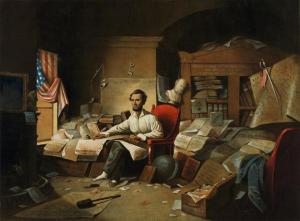

This volume is addressed to three classes of readers; to the layman, to the amateur photographer, and to the professional artist. To the latter it speaks more in the temper of the studio discussion than in the spirit didactic. But, emboldened by the friendliness the profession always exhibits toward any serious word in art, the writer is moved to believe that the matters herein discussed may be found worthy of the artist's attention—perhaps of his question. For that reason the tone here and there is argumentative. The question of balance has never been reduced to a theory or stated as a set of principles which could be sustained by anything more than example, which, as a working basis must require reconstruction with every change of subject. Other forms of construction have been sifted down in a search for the governing principle,—a substitution for the “rule and example.” To the student and the amateur, therefore, it must be said this is not a “how-to-do” book. The number of these is legion, especially in painting, known to all students, wherein the matter is didactic and usually set forth with little or no argument. Such volumes are published because of the great demand and are demanded because the student, in his haste, will not stop for principles, and think it out. He will have a rule for each case; and when his direct question has been answered with a principle, he still inquires, “Well, what shall I do here?” Why preach the golden rule of harmony as an abstraction, when inharmony is the concrete sin to be destroyed. We reach the former by elimination. Whatever commandments this book contains, therefore, are the shalt nots. As the problems to the maker of pictures by photography are the same as those of the painter and the especial ambition of the former's art is to be painter-like, separations have been thought unnecessary in the address of the text. It is the best wish of the author that photography, following painting in her essential principles as she does, may prove herself a well met companion along art's highway,—seekers together, at arm's length, and in defined limits, of the same goal.

This volume is addressed to three classes of readers; to the layman, to the amateur photographer, and to the professional artist. To the latter it speaks more in the temper of the studio discussion than in the spirit didactic. But, emboldened by the friendliness the profession always exhibits toward any serious word in art, the writer is moved to believe that the matters herein discussed may be found worthy of the artist's attention—perhaps of his question. For that reason the tone here and there is argumentative. The question of balance has never been reduced to a theory or stated as a set of principles which could be sustained by anything more than example, which, as a working basis must require reconstruction with every change of subject. Other forms of construction have been sifted down in a search for the governing principle,—a substitution for the “rule and example.” To the student and the amateur, therefore, it must be said this is not a “how-to-do” book. The number of these is legion, especially in painting, known to all students, wherein the matter is didactic and usually set forth with little or no argument. Such volumes are published because of the great demand and are demanded because the student, in his haste, will not stop for principles, and think it out. He will have a rule for each case; and when his direct question has been answered with a principle, he still inquires, “Well, what shall I do here?” Why preach the golden rule of harmony as an abstraction, when inharmony is the concrete sin to be destroyed. We reach the former by elimination. Whatever commandments this book contains, therefore, are the shalt nots. As the problems to the maker of pictures by photography are the same as those of the painter and the especial ambition of the former's art is to be painter-like, separations have been thought unnecessary in the address of the text. It is the best wish of the author that photography, following painting in her essential principles as she does, may prove herself a well met companion along art's highway,—seekers together, at arm's length, and in defined limits, of the same goal.