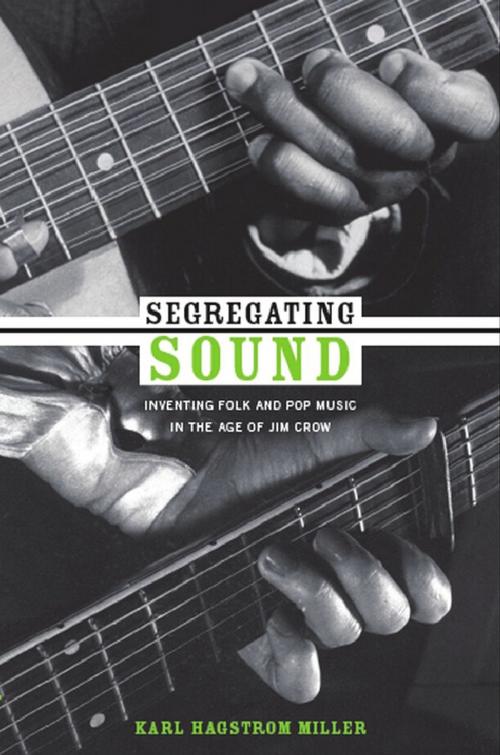

Segregating Sound

Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow

Nonfiction, Entertainment, Music, Music Styles, Jazz & Blues, Blues, Country| Author: | Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, Karl Hagstrom Miller | ISBN: | 9780822392705 |

| Publisher: | Duke University Press | Publication: | February 11, 2010 |

| Imprint: | Duke University Press Books | Language: | English |

| Author: | Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, Karl Hagstrom Miller |

| ISBN: | 9780822392705 |

| Publisher: | Duke University Press |

| Publication: | February 11, 2010 |

| Imprint: | Duke University Press Books |

| Language: | English |

In Segregating Sound, Karl Hagstrom Miller argues that the categories that we have inherited to think and talk about southern music bear little relation to the ways that southerners long played and heard music. Focusing on the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth, Miller chronicles how southern music—a fluid complex of sounds and styles in practice—was reduced to a series of distinct genres linked to particular racial and ethnic identities. The blues were African American. Rural white southerners played country music. By the 1920s, these depictions were touted in folk song collections and the catalogs of “race” and “hillbilly” records produced by the phonograph industry. Such links among race, region, and music were new. Black and white artists alike had played not only blues, ballads, ragtime, and string band music, but also nationally popular sentimental ballads, minstrel songs, Tin Pan Alley tunes, and Broadway hits.

In a cultural history filled with musicians, listeners, scholars, and business people, Miller describes how folklore studies and the music industry helped to create a “musical color line,” a cultural parallel to the physical color line that came to define the Jim Crow South. Segregated sound emerged slowly through the interactions of southern and northern musicians, record companies that sought to penetrate new markets across the South and the globe, and academic folklorists who attempted to tap southern music for evidence about the history of human civilization. Contending that people’s musical worlds were defined less by who they were than by the music that they heard, Miller challenges assumptions about the relation of race, music, and the market.

In Segregating Sound, Karl Hagstrom Miller argues that the categories that we have inherited to think and talk about southern music bear little relation to the ways that southerners long played and heard music. Focusing on the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth, Miller chronicles how southern music—a fluid complex of sounds and styles in practice—was reduced to a series of distinct genres linked to particular racial and ethnic identities. The blues were African American. Rural white southerners played country music. By the 1920s, these depictions were touted in folk song collections and the catalogs of “race” and “hillbilly” records produced by the phonograph industry. Such links among race, region, and music were new. Black and white artists alike had played not only blues, ballads, ragtime, and string band music, but also nationally popular sentimental ballads, minstrel songs, Tin Pan Alley tunes, and Broadway hits.

In a cultural history filled with musicians, listeners, scholars, and business people, Miller describes how folklore studies and the music industry helped to create a “musical color line,” a cultural parallel to the physical color line that came to define the Jim Crow South. Segregated sound emerged slowly through the interactions of southern and northern musicians, record companies that sought to penetrate new markets across the South and the globe, and academic folklorists who attempted to tap southern music for evidence about the history of human civilization. Contending that people’s musical worlds were defined less by who they were than by the music that they heard, Miller challenges assumptions about the relation of race, music, and the market.