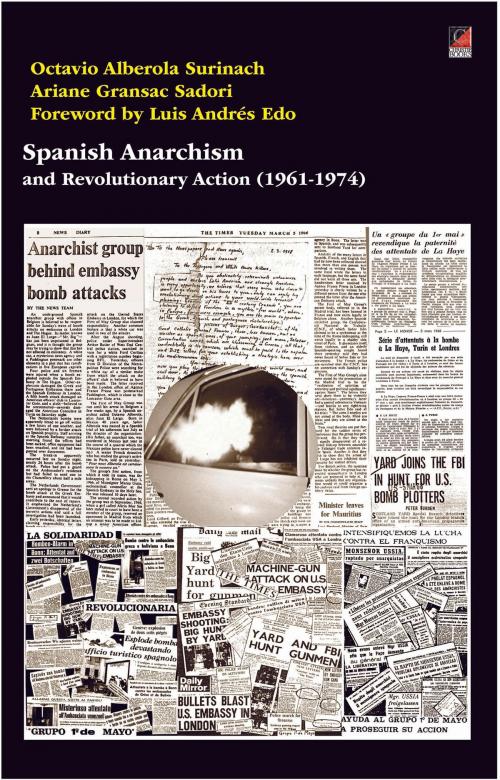

Spanish Anarchism and Revolutionary Action (1961-1974)

Nonfiction, History, Revolutionary, Spain & Portugal, Modern, 20th Century| Author: | Octavio Alberola, Ariane Gransac | ISBN: | 1230000273184 |

| Publisher: | ChristieBooks | Publication: | October 10, 2014 |

| Imprint: | ChristieBooks | Language: | English |

| Author: | Octavio Alberola, Ariane Gransac |

| ISBN: | 1230000273184 |

| Publisher: | ChristieBooks |

| Publication: | October 10, 2014 |

| Imprint: | ChristieBooks |

| Language: | English |

This account of the role of anarchist activism in Europe between 1961 and 1974, by two of the principal protagonists in the events they describe, was first published in Spanish and French in 1975. To this day it remains essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the history and development of the libertarian opposition to the Franco Dictatorship subsequent to the urban and rural guerrilla tactics as practised by Sabate, Facerias, and Caraquemada, etc. It examines the birth of the clandestine 'Defensa Interior' Section of the Spanish Libertarian Movement (MLE - CNT-FAI-FIJL) through to 'The First of May Group' and its influence on — and links with — other European action groups of the later 1960s and early 1970s, groups such as 'The Angry Brigade', the 'Grupos Autonomos de Combate — GAC', 2nd June Group, the Movimiento Iberico de Liberacion — 'MIL', Gruppo d'Azione Partigiano – GAP, Grupos de Accion Revolucionaria Internacional — 'GARI', etc.

The story begins in late 1961 with the creation of Sección DEFENSA INTERIOR (DI), the clandestine planning and action organisation set up at the Limoges Congress in France by the Defence Commission of the recently reunited three wings of the exiled Spanish libertarian movement (MLE — Movimiento Libertario Español) — the CNT, the Spanish anarcho-syndicalist trade union; the FAI, the Iberian Anarchist Federation, and the FIJL, the Iberian Federation of Libertarian Youth. One of the DI's principal objectives of the DI was to organise and carry out attempts on the life of General Franco. Its other role was to generate examples of resistance by means of propaganda by deed. The DI's short-term objectives were: to remind the world, unremittingly, that Franco’s brutal and repressive dictatorship had not only survived WWII but was now flourishing through tourism and US financial and diplomatic support; to provide solidarity for those continuining the struggle within Spain; to polarise public opinion and focus attention on the plight of the steadily increasing number of political prisoners in Franco’s jails; to interrupt the conduct of Francoist commercial and diplomatic life; undermine its financial basis — tourism; to take the struggle against Franco into the international sphere by showing the world that Franco did not enjoy unchallenged power and that there was resistance to the regime within and beyond Spain’s borders.

The longer-term objective, taking into account the specific historical and cultural context of the time — with the recent overthrow of Latin American dictators Fulgencio Batista and Rafael Trujillo and the rising industrial and student militancy within Spain itself, which could have been interpreted as a potentially pre-insurgent mood — was the destabilising and overthrow of the regime. The ultimate aim, however, was to kill Franco — the the keystone of the system and the root cause of 28 years of murder, misery and oppression in Spain. Franco had no appointed successor and the right — the Army, Church, the Falange, the Carlists and the Opus Dei were divided. If Franco could be removed, it was hoped new, progressive and democratic forces would be introduced onto the political stage.

But, the contemporaneous French-based DI’s direct action campaign against Francoist targets — actions which were largely symbolic and in which no one was killed or even seriously injured — coupled with the ruthless and indiscriminate terror attacks on French civilians and the attempts on the life of French president General de Gaulle by the Spain-based ultra-right-wing French settler's Organisation armée secrèt (OAS), exacerbated Franco-Spanish diplomatic tensions and led to an informal, collaborative, quid pro quo between the French and Spanish security services and a major clampdown on the OAS organisation in Spain and on FIJL activists in France. Political and psychological pressure was also brought to bear on the comfortably-placed, highly-compromised and bureaucratic CNT leadership .

This account of the role of anarchist activism in Europe between 1961 and 1974, by two of the principal protagonists in the events they describe, was first published in Spanish and French in 1975. To this day it remains essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the history and development of the libertarian opposition to the Franco Dictatorship subsequent to the urban and rural guerrilla tactics as practised by Sabate, Facerias, and Caraquemada, etc. It examines the birth of the clandestine 'Defensa Interior' Section of the Spanish Libertarian Movement (MLE - CNT-FAI-FIJL) through to 'The First of May Group' and its influence on — and links with — other European action groups of the later 1960s and early 1970s, groups such as 'The Angry Brigade', the 'Grupos Autonomos de Combate — GAC', 2nd June Group, the Movimiento Iberico de Liberacion — 'MIL', Gruppo d'Azione Partigiano – GAP, Grupos de Accion Revolucionaria Internacional — 'GARI', etc.

The story begins in late 1961 with the creation of Sección DEFENSA INTERIOR (DI), the clandestine planning and action organisation set up at the Limoges Congress in France by the Defence Commission of the recently reunited three wings of the exiled Spanish libertarian movement (MLE — Movimiento Libertario Español) — the CNT, the Spanish anarcho-syndicalist trade union; the FAI, the Iberian Anarchist Federation, and the FIJL, the Iberian Federation of Libertarian Youth. One of the DI's principal objectives of the DI was to organise and carry out attempts on the life of General Franco. Its other role was to generate examples of resistance by means of propaganda by deed. The DI's short-term objectives were: to remind the world, unremittingly, that Franco’s brutal and repressive dictatorship had not only survived WWII but was now flourishing through tourism and US financial and diplomatic support; to provide solidarity for those continuining the struggle within Spain; to polarise public opinion and focus attention on the plight of the steadily increasing number of political prisoners in Franco’s jails; to interrupt the conduct of Francoist commercial and diplomatic life; undermine its financial basis — tourism; to take the struggle against Franco into the international sphere by showing the world that Franco did not enjoy unchallenged power and that there was resistance to the regime within and beyond Spain’s borders.

The longer-term objective, taking into account the specific historical and cultural context of the time — with the recent overthrow of Latin American dictators Fulgencio Batista and Rafael Trujillo and the rising industrial and student militancy within Spain itself, which could have been interpreted as a potentially pre-insurgent mood — was the destabilising and overthrow of the regime. The ultimate aim, however, was to kill Franco — the the keystone of the system and the root cause of 28 years of murder, misery and oppression in Spain. Franco had no appointed successor and the right — the Army, Church, the Falange, the Carlists and the Opus Dei were divided. If Franco could be removed, it was hoped new, progressive and democratic forces would be introduced onto the political stage.

But, the contemporaneous French-based DI’s direct action campaign against Francoist targets — actions which were largely symbolic and in which no one was killed or even seriously injured — coupled with the ruthless and indiscriminate terror attacks on French civilians and the attempts on the life of French president General de Gaulle by the Spain-based ultra-right-wing French settler's Organisation armée secrèt (OAS), exacerbated Franco-Spanish diplomatic tensions and led to an informal, collaborative, quid pro quo between the French and Spanish security services and a major clampdown on the OAS organisation in Spain and on FIJL activists in France. Political and psychological pressure was also brought to bear on the comfortably-placed, highly-compromised and bureaucratic CNT leadership .