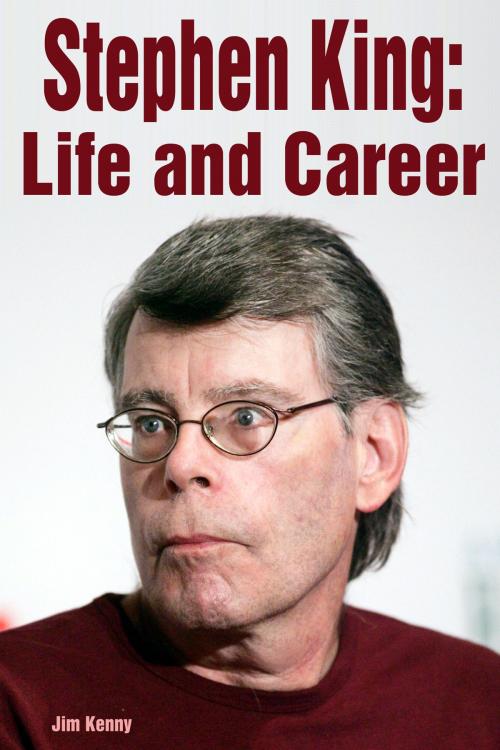

Stephen King: Life and Career

Biography & Memoir, Business, Reference, Entertainment & Performing Arts| Author: | Jim Kenny | ISBN: | 1230000287624 |

| Publisher: | Jim Kenny | Publication: | December 23, 2014 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Jim Kenny |

| ISBN: | 1230000287624 |

| Publisher: | Jim Kenny |

| Publication: | December 23, 2014 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Stephen King has written a lot of books – at 56 novels, he's closing in on Agatha Christie – some of which have been great, some of which less so. Still, he says, when people say, "Steve, your books are uneven", he's confident "there's good stuff in all of 'em". Now and then, a story lingers in his mind long after it's published. When fans ask what happened to Charlie McGee in Firestarter, for example, King isn't interested. But when they ask what happened to Danny Torrance, the boy from The Shining, he always found himself wondering. Specifically: what the story would have looked like if Danny's father – mad "white-knuckle alcoholic" Jack Torrance – had "found AA. And I thought, well, let's find out."

At 65, King is a big, shaggy presence, towering despite his slightly stooped shoulders and with an air of affable amusement at the vastness of his success and all that comes with it. We are at a house in Maine that his assistant, opening the door, drily refers to as "spare"; it's one of several King properties in the area, on a lake, and designated vaguely as a summer house. It is at the end of a long, deserted road, surrounded by woodland and in a GPS dead zone; this, after a week of rereading King novels, is unrelaxing. Rather than spend the night in a remote B&B near his house, as his publisher suggests, I stay in Portland, 100 miles away, in a hotel where there are lights and cars going by, and people to hear you scream. "Really?" King says when I mention my unease, and grins. "Good."

Doctor Sleep, his 56th novel, revisits Danny in adulthood, when he has become an alcoholic drifter haunted by the memory of his raging father. The Shining had such resonance – in part because of Kubrick's film, which King disliked – that one returns to the characters with a sense of deep familiarity. In the sequel, Wendy, the mother, is dead from lung cancer and Danny is alone, working in a hospice in a small town, where his paranormal talents help people towards a peaceful death. When Abra, a telepathic child, pushes into his consciousness asking for help, Danny gets sucked back into the terrain of his childhood, battling a bunch of centuries-old serial killers disguised as RV-driving pensioners (it is sometimes easy to overlook how slyly funny King is) who literally feed off the pain of others. "When the disaster was big enough," King writes, "agony and violent death had an enriching quality." They get a big kick out of 9/11.

It is scary, of course: a woman with a tusk instead of teeth pops up periodically to hang at second-floor window level and startle the bejesus out of you. And without labouring the point, it has good allegorical bones: the sick buzz one gets from consuming the grisliest news stories. It also captures the reality of a recovering alcoholic, a state with which King is intimately familiar. "The hungover eye," he writes, "had a weird ability to find the ugliest things in any given landscape." Danny turns his life around and starts going to AA meetings, where, King writes, he discovers that memories are the "real ghosts". It is a book as extravagantly inventive as any in King's pantheon, and a careful study of self-haunting: "You take yourself with you, wherever you go."

King has been sober for decades, ever since his family staged an intervention in the late 1980s. If he hesitated to write in this much depth about AA, it was only because he wanted to get it right. "The only thing is to write the truth. To write what you know about any particular situation. And I never say to anybody, 'This is all from my experience in AA,' because you don't say that." It was King's 36-year-old son, Owen, who, after reading the first draft of Doctor Sleep, told him there was something missing. "He said that the scene he remembered best from The Shining was the one where Jack Torrance and his friend are out drunk one night and they hit a bicycle and think they've killed a kid. And they say, 'That's the end; we're not going to drink any more.' And Owen said, 'There's no scene that's comparable to that in Doctor Sleep. You ought to see Dan at his worst.' And, as usual, Owen was right."

The scene King put in, would, in subsequent drafts, go on to drive the whole story: Danny waking up next to a one-night stand, stealing her money and leaving her infant son wandering about with a full nappy, reaching for drugs on the coffee table. "And I think every alcoholic has a story comparable to that. Something where you actually hit rock bottom."

In his case?

"I don't have anything as dramatic. Of course, in a novel, you're looking for something that's really harsh. Harshly lit. For me, when I look back, the thing that I remember is being at one of my son's Little League games with a can of beer in a paper bag, and the coach coming over to me and saying, 'If that's an alcoholic beverage, you're going to have to leave.' That was where I said to myself, 'That's something I'll never be able to tell anybody else. I'll keep that one to myself.' I drew on that memory."

In Doctor Sleep, Danny fights his past with a more profound sense of terror than anything the woman with the tusk can bring on. The tentacle reach of history has always interested King – "What's inside your head grows. And you don't have any sense of proportion until you see how other people react to it" – as has the futility of trying to escape it. "Take Dan Torrance, who is the child of an alcoholic, child of a dysfunctional family, abusive father, and he says, as people do, 'I'm never going to be like my father; I'm never going to be like my mother.' And then you grow up and find yourself with a beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other, and maybe you're walking the kiddies around. And I wanted to see what would happen with that."

For a while, King would write sober during the day and edit what he had set down, while drinking, at night. "As time went on, I started to fumble a lot of the balls. I had a busy public life and a lot of those things got a bit ragged by the end." Did he, like Danny, go to bars and get in fights?

Stephen King has written a lot of books – at 56 novels, he's closing in on Agatha Christie – some of which have been great, some of which less so. Still, he says, when people say, "Steve, your books are uneven", he's confident "there's good stuff in all of 'em". Now and then, a story lingers in his mind long after it's published. When fans ask what happened to Charlie McGee in Firestarter, for example, King isn't interested. But when they ask what happened to Danny Torrance, the boy from The Shining, he always found himself wondering. Specifically: what the story would have looked like if Danny's father – mad "white-knuckle alcoholic" Jack Torrance – had "found AA. And I thought, well, let's find out."

At 65, King is a big, shaggy presence, towering despite his slightly stooped shoulders and with an air of affable amusement at the vastness of his success and all that comes with it. We are at a house in Maine that his assistant, opening the door, drily refers to as "spare"; it's one of several King properties in the area, on a lake, and designated vaguely as a summer house. It is at the end of a long, deserted road, surrounded by woodland and in a GPS dead zone; this, after a week of rereading King novels, is unrelaxing. Rather than spend the night in a remote B&B near his house, as his publisher suggests, I stay in Portland, 100 miles away, in a hotel where there are lights and cars going by, and people to hear you scream. "Really?" King says when I mention my unease, and grins. "Good."

Doctor Sleep, his 56th novel, revisits Danny in adulthood, when he has become an alcoholic drifter haunted by the memory of his raging father. The Shining had such resonance – in part because of Kubrick's film, which King disliked – that one returns to the characters with a sense of deep familiarity. In the sequel, Wendy, the mother, is dead from lung cancer and Danny is alone, working in a hospice in a small town, where his paranormal talents help people towards a peaceful death. When Abra, a telepathic child, pushes into his consciousness asking for help, Danny gets sucked back into the terrain of his childhood, battling a bunch of centuries-old serial killers disguised as RV-driving pensioners (it is sometimes easy to overlook how slyly funny King is) who literally feed off the pain of others. "When the disaster was big enough," King writes, "agony and violent death had an enriching quality." They get a big kick out of 9/11.

It is scary, of course: a woman with a tusk instead of teeth pops up periodically to hang at second-floor window level and startle the bejesus out of you. And without labouring the point, it has good allegorical bones: the sick buzz one gets from consuming the grisliest news stories. It also captures the reality of a recovering alcoholic, a state with which King is intimately familiar. "The hungover eye," he writes, "had a weird ability to find the ugliest things in any given landscape." Danny turns his life around and starts going to AA meetings, where, King writes, he discovers that memories are the "real ghosts". It is a book as extravagantly inventive as any in King's pantheon, and a careful study of self-haunting: "You take yourself with you, wherever you go."

King has been sober for decades, ever since his family staged an intervention in the late 1980s. If he hesitated to write in this much depth about AA, it was only because he wanted to get it right. "The only thing is to write the truth. To write what you know about any particular situation. And I never say to anybody, 'This is all from my experience in AA,' because you don't say that." It was King's 36-year-old son, Owen, who, after reading the first draft of Doctor Sleep, told him there was something missing. "He said that the scene he remembered best from The Shining was the one where Jack Torrance and his friend are out drunk one night and they hit a bicycle and think they've killed a kid. And they say, 'That's the end; we're not going to drink any more.' And Owen said, 'There's no scene that's comparable to that in Doctor Sleep. You ought to see Dan at his worst.' And, as usual, Owen was right."

The scene King put in, would, in subsequent drafts, go on to drive the whole story: Danny waking up next to a one-night stand, stealing her money and leaving her infant son wandering about with a full nappy, reaching for drugs on the coffee table. "And I think every alcoholic has a story comparable to that. Something where you actually hit rock bottom."

In his case?

"I don't have anything as dramatic. Of course, in a novel, you're looking for something that's really harsh. Harshly lit. For me, when I look back, the thing that I remember is being at one of my son's Little League games with a can of beer in a paper bag, and the coach coming over to me and saying, 'If that's an alcoholic beverage, you're going to have to leave.' That was where I said to myself, 'That's something I'll never be able to tell anybody else. I'll keep that one to myself.' I drew on that memory."

In Doctor Sleep, Danny fights his past with a more profound sense of terror than anything the woman with the tusk can bring on. The tentacle reach of history has always interested King – "What's inside your head grows. And you don't have any sense of proportion until you see how other people react to it" – as has the futility of trying to escape it. "Take Dan Torrance, who is the child of an alcoholic, child of a dysfunctional family, abusive father, and he says, as people do, 'I'm never going to be like my father; I'm never going to be like my mother.' And then you grow up and find yourself with a beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other, and maybe you're walking the kiddies around. And I wanted to see what would happen with that."

For a while, King would write sober during the day and edit what he had set down, while drinking, at night. "As time went on, I started to fumble a lot of the balls. I had a busy public life and a lot of those things got a bit ragged by the end." Did he, like Danny, go to bars and get in fights?