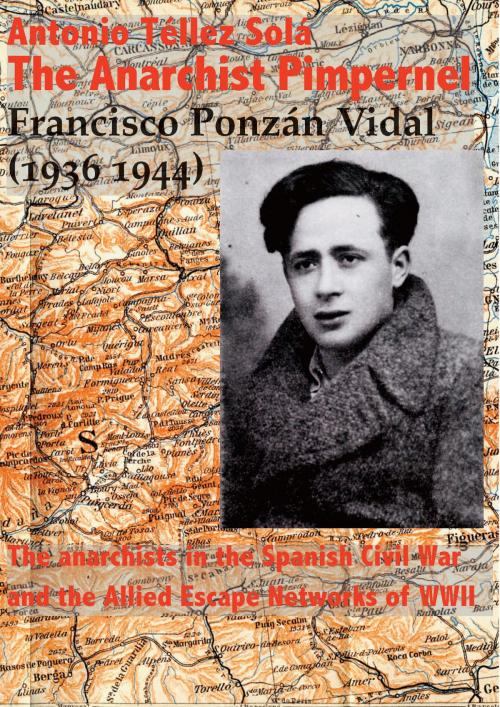

The Anarchist Pimpernel Francisco Ponzán Vidal (1936-1944).

The anarchists in the Spanish Civil War and the Allied Escape Networks of WWII

Nonfiction, History, Military, World War II, Biography & Memoir, Political, Historical| Author: | Antonio Téllez | ISBN: | 1230000274034 |

| Publisher: | ChristieBooks | Publication: | October 14, 2014 |

| Imprint: | ChristieBooks | Language: | English |

| Author: | Antonio Téllez |

| ISBN: | 1230000274034 |

| Publisher: | ChristieBooks |

| Publication: | October 14, 2014 |

| Imprint: | ChristieBooks |

| Language: | English |

The anarchists in the secret war against Francoism, Nazism, and the escape and evasion lines of WWII. THIS BOOK, now seeing publication in an English translation, was begun in 1973 and concluded in 1978. It deals with two of the bloodiest periods of this century and the struggle waged by men and women with an enduring aspiration to freedom and to a new and more humane society. These individuals put their lives on the line in the fight against all manner of tyranny, black, blue or red: the Spanish civil War (1936–1939), the overture to the Second World War (1939-1945) that ravaged our planet, in which they played their part.

This history is related herein through the stories of two chief protagonists, Francisco Ponzán Vidal and Agustín Remiro Manero, but it is dedicated to all who, like them, never strayed from their course and lost their lives in the process.

Two Aragonese, Ponzán and Remiro: the first born in Oviedo (Asturias) on 3 March 1911, but Aragonese “by adoption,” in that he always regarded himself as such; the second born in Epila (Zaragoza) on 28 August 1904. Their lives followed parallel courses in every respect. Both were anarcho-syndicalists to the last, they fought shoulder to shoulder in the Spanish Civil War and during the Second World War in a battle without quarter against the Franco regime and alongside the Allies against Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, and both died an ugly, untimely death. Remiro met his end in the Spanish capital of Madrid on 21 June 1942 at the hands of the Francoists, while the Nazis in the Toulouse area of France murdered Ponzán on 17 August 1944. Remiro had not quite reached his 38th birthday; Ponzán was 33.

The name of Agustín Remiro, a peasant guerilla sans pareil, is practically unknown today.

Francisco Ponzán is less obscure due to his sister Pilar’s efforts to keep his memory alive. Thanks to her determination, a number of very incomplete articles and essays saw publication from 1945 on. Several chapters of this book are the direct testimony of Pilar Ponzán,

The historical narration of developments during the two wars does not follow the classical model here. War histories, as is well known, tend to dwell on the high-ranking officers rather than the rank and file soldiers who are the main victims: the latter feature only in the statistical figures for the dead, wounded and disabled, and it is to their memory that the monuments to the “Unknown Soldier” have been erected.

By contrast, this volume valorizes the worker, peasant and intellectual militants—not military men but people who, when they had no choice but to fight, proved to be superb fighters, albeit with very special characteristics. Their main weapon was not the pistol, rifle or machine-gun – although they used these too – but rather minds committed to serving a precept of justice and an invincible opposition to tyranny in any guise. Ttheir enduring aim was to champion freedom, a notion rather undervalued in those years of an appeasement and universal cowardice that was moral rather than physical.

They were exceptional and exemplary figures and yet they have defied understanding and been denied recognition. The names cited here are not the only ones, of that we may be sure, but they are representative of all who fought the same fight, prompted by the very same ardour and not knowing the meaning of the word surrender, and likewise of all who continue to fight the good fight across the five continents, for their war goes on. Our people generally operate in the shadowy underground, and it is exceedingly difficult to probe their secret past.

When they were “on active service,” these young and not-so-young people were altruists who placed all their energies in the service of humanity. They discovered enemies all round, even within their own ranks, but could not be swayed from their chosen course. This course was not always one they might have chosen had they other options, but when all is said and done, they held it to be their best way of serving the good of all under the circumstances.

The anarchists in the secret war against Francoism, Nazism, and the escape and evasion lines of WWII. THIS BOOK, now seeing publication in an English translation, was begun in 1973 and concluded in 1978. It deals with two of the bloodiest periods of this century and the struggle waged by men and women with an enduring aspiration to freedom and to a new and more humane society. These individuals put their lives on the line in the fight against all manner of tyranny, black, blue or red: the Spanish civil War (1936–1939), the overture to the Second World War (1939-1945) that ravaged our planet, in which they played their part.

This history is related herein through the stories of two chief protagonists, Francisco Ponzán Vidal and Agustín Remiro Manero, but it is dedicated to all who, like them, never strayed from their course and lost their lives in the process.

Two Aragonese, Ponzán and Remiro: the first born in Oviedo (Asturias) on 3 March 1911, but Aragonese “by adoption,” in that he always regarded himself as such; the second born in Epila (Zaragoza) on 28 August 1904. Their lives followed parallel courses in every respect. Both were anarcho-syndicalists to the last, they fought shoulder to shoulder in the Spanish Civil War and during the Second World War in a battle without quarter against the Franco regime and alongside the Allies against Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, and both died an ugly, untimely death. Remiro met his end in the Spanish capital of Madrid on 21 June 1942 at the hands of the Francoists, while the Nazis in the Toulouse area of France murdered Ponzán on 17 August 1944. Remiro had not quite reached his 38th birthday; Ponzán was 33.

The name of Agustín Remiro, a peasant guerilla sans pareil, is practically unknown today.

Francisco Ponzán is less obscure due to his sister Pilar’s efforts to keep his memory alive. Thanks to her determination, a number of very incomplete articles and essays saw publication from 1945 on. Several chapters of this book are the direct testimony of Pilar Ponzán,

The historical narration of developments during the two wars does not follow the classical model here. War histories, as is well known, tend to dwell on the high-ranking officers rather than the rank and file soldiers who are the main victims: the latter feature only in the statistical figures for the dead, wounded and disabled, and it is to their memory that the monuments to the “Unknown Soldier” have been erected.

By contrast, this volume valorizes the worker, peasant and intellectual militants—not military men but people who, when they had no choice but to fight, proved to be superb fighters, albeit with very special characteristics. Their main weapon was not the pistol, rifle or machine-gun – although they used these too – but rather minds committed to serving a precept of justice and an invincible opposition to tyranny in any guise. Ttheir enduring aim was to champion freedom, a notion rather undervalued in those years of an appeasement and universal cowardice that was moral rather than physical.

They were exceptional and exemplary figures and yet they have defied understanding and been denied recognition. The names cited here are not the only ones, of that we may be sure, but they are representative of all who fought the same fight, prompted by the very same ardour and not knowing the meaning of the word surrender, and likewise of all who continue to fight the good fight across the five continents, for their war goes on. Our people generally operate in the shadowy underground, and it is exceedingly difficult to probe their secret past.

When they were “on active service,” these young and not-so-young people were altruists who placed all their energies in the service of humanity. They discovered enemies all round, even within their own ranks, but could not be swayed from their chosen course. This course was not always one they might have chosen had they other options, but when all is said and done, they held it to be their best way of serving the good of all under the circumstances.