The Evolution of Man (Complete)

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel | ISBN: | 9781465548931 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel |

| ISBN: | 9781465548931 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

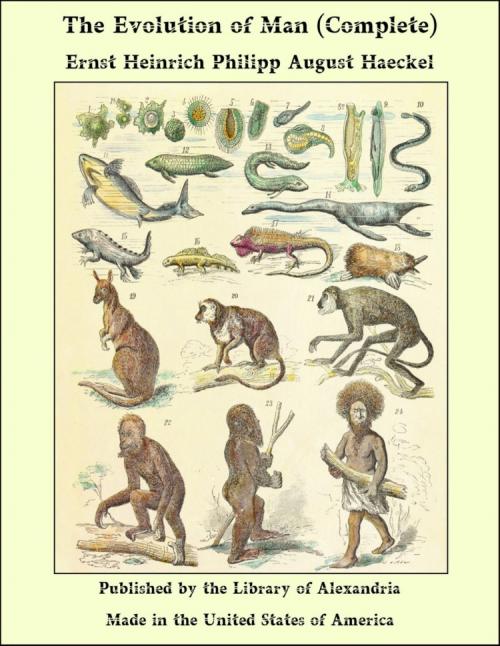

The work which we now place within the reach of every reader of the English tongue is one of the finest productions of its distinguished author. The first edition appeared in 1874. At that time the conviction of man's natural evolution was even less advanced in Germany than in England, and the work raised a storm of controversy. Theologians—forgetting the commonest facts of our individual development—spoke with the most profound disdain of the theory that a Luther or a Goethe could be the outcome of development from a tiny speck of protoplasm. The work, one of the most distinguished of them said, was "a fleck of shame on the escutcheon of Germany." To-day its conclusion is accepted by influential clerics, such as the Dean of Westminster, and by almost every biologist and anthropologist of distinction in Europe. Evolution is not a laboriously reached conclusion, but a guiding truth, in biological literature to-day. There was ample evidence to substantiate the conclusion even in the first edition of the book. But fresh facts have come to light in each decade, always enforcing the general truth of man's evolution, and at times making clearer the line of development. Professor Haeckel embodied these in successive editions of his work. In the fifth edition, of which this is a translation, reference will be found to the very latest facts bearing on the evolution of man, such as the discovery of the remarkable effect of mixing human blood with that of the anthropoid ape. Moreover, the ample series of illustrations has been considerably improved and enlarged; there is no scientific work published, at a price remotely approaching that of the present edition, with so abundant and excellent a supply of illustrations. When it was issued in Germany, a few years ago, a distinguished biologist wrote in the Frankfurter Zeitung that it would secure immortality for its author, the most notable critic of the idea of immortality. And the Daily Telegraph reviewer described the English version as a "handsome edition of Haeckel's monumental work," and "an issue worthy of the subject and the author

The work which we now place within the reach of every reader of the English tongue is one of the finest productions of its distinguished author. The first edition appeared in 1874. At that time the conviction of man's natural evolution was even less advanced in Germany than in England, and the work raised a storm of controversy. Theologians—forgetting the commonest facts of our individual development—spoke with the most profound disdain of the theory that a Luther or a Goethe could be the outcome of development from a tiny speck of protoplasm. The work, one of the most distinguished of them said, was "a fleck of shame on the escutcheon of Germany." To-day its conclusion is accepted by influential clerics, such as the Dean of Westminster, and by almost every biologist and anthropologist of distinction in Europe. Evolution is not a laboriously reached conclusion, but a guiding truth, in biological literature to-day. There was ample evidence to substantiate the conclusion even in the first edition of the book. But fresh facts have come to light in each decade, always enforcing the general truth of man's evolution, and at times making clearer the line of development. Professor Haeckel embodied these in successive editions of his work. In the fifth edition, of which this is a translation, reference will be found to the very latest facts bearing on the evolution of man, such as the discovery of the remarkable effect of mixing human blood with that of the anthropoid ape. Moreover, the ample series of illustrations has been considerably improved and enlarged; there is no scientific work published, at a price remotely approaching that of the present edition, with so abundant and excellent a supply of illustrations. When it was issued in Germany, a few years ago, a distinguished biologist wrote in the Frankfurter Zeitung that it would secure immortality for its author, the most notable critic of the idea of immortality. And the Daily Telegraph reviewer described the English version as a "handsome edition of Haeckel's monumental work," and "an issue worthy of the subject and the author