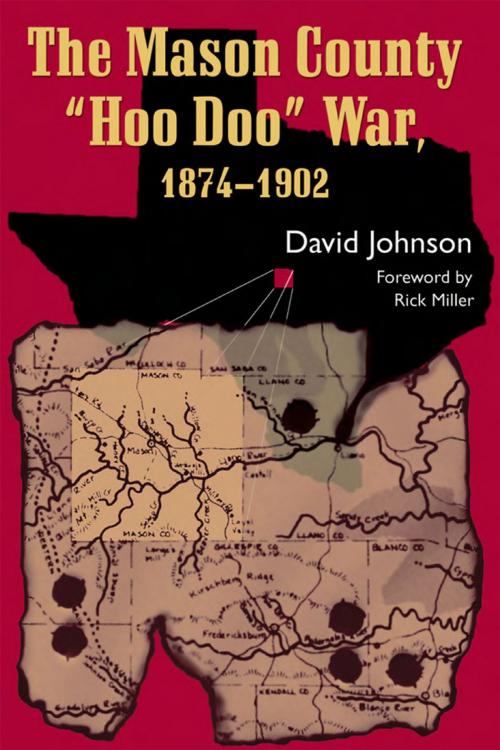

The Mason County "Hoo Doo" War, 1874-1902

Nonfiction, History, Americas, United States, 19th Century, Social & Cultural Studies, True Crime, Murder| Author: | David Johnson | ISBN: | 9781574413977 |

| Publisher: | University of North Texas Press | Publication: | February 15, 2006 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | David Johnson |

| ISBN: | 9781574413977 |

| Publisher: | University of North Texas Press |

| Publication: | February 15, 2006 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Post-Reconstruction Texas in the mid-1870s was still relatively primitive, with communities isolated from each other in a largely open-range environment. Cattlemen owned herds of cattle in numerous counties while brand laws remained local. Friction arose when the nonresident stockmen attempted to gather their cattle, and mavericking was common. Law enforcement at the local level could cope with handling local drunks, collecting taxes, and attending the courts when in session, but when an outrageous crime occurred, or depredations in a community were at a level that severely taxed or overwhelmed the local sheriff, there was seldom any other recourse except a vigilante movement. With such a fragile hold on civilization in these communities, it is not difficult to understand how a blood feud could occur. During 1874 the Hoo Doo War erupted in the Texas Hill Country of Mason County, and for the remainder of the century violence and fear ruled the region in a rising tide of hatred and revenge. It is widely considered the most bitter feud in Texas history. Traditionally the feud is said to have begun with the intention of protecting the families, property and livelihood of the largely agrarian settlers in Mason and Llano counties. The truth is far more sinister. Evidence shows that the mob was contaminated from the outset by a criminal element, a fact the participants failed to recognize. They believed they were above the law. They were not above vengeance. The feud began in 1874 with the rise of the mob under Sheriff John Clark, but it was not until the premeditated murder of rancher Timothy Williamson in the spring of 1875, a murder orchestrated by Sheriff Clark, that the violence escalated out of control. His death drew former Texas Ranger Scott Cooley to the region seeking justice, and when the courts failed, he began a vendetta to avenge his friend. In the ensuing months, Sheriff Clark used the mob to secure his political position by ambushing ranchers George Gladden and Moses Baird, which drew gunfighters such as John Ringo into the violence. As more men were killed, new forces joined the spiral of death. Local and state officials proved powerless, and it was not until the early 1900s that the feud burned itself out. Johnson has proven a diligent researcher in locating information concerning the Hoo Doo War. Using contemporary newspaper accounts, letters, diaries, and official reports, he analyzes the myths and legends surrounding the feud and presents the unvarnished truth of what happened in Mason County. This book is the definitive account of the Hoo Doo War, as well as a case study in frontier violence of the bloodiest kind.

Post-Reconstruction Texas in the mid-1870s was still relatively primitive, with communities isolated from each other in a largely open-range environment. Cattlemen owned herds of cattle in numerous counties while brand laws remained local. Friction arose when the nonresident stockmen attempted to gather their cattle, and mavericking was common. Law enforcement at the local level could cope with handling local drunks, collecting taxes, and attending the courts when in session, but when an outrageous crime occurred, or depredations in a community were at a level that severely taxed or overwhelmed the local sheriff, there was seldom any other recourse except a vigilante movement. With such a fragile hold on civilization in these communities, it is not difficult to understand how a blood feud could occur. During 1874 the Hoo Doo War erupted in the Texas Hill Country of Mason County, and for the remainder of the century violence and fear ruled the region in a rising tide of hatred and revenge. It is widely considered the most bitter feud in Texas history. Traditionally the feud is said to have begun with the intention of protecting the families, property and livelihood of the largely agrarian settlers in Mason and Llano counties. The truth is far more sinister. Evidence shows that the mob was contaminated from the outset by a criminal element, a fact the participants failed to recognize. They believed they were above the law. They were not above vengeance. The feud began in 1874 with the rise of the mob under Sheriff John Clark, but it was not until the premeditated murder of rancher Timothy Williamson in the spring of 1875, a murder orchestrated by Sheriff Clark, that the violence escalated out of control. His death drew former Texas Ranger Scott Cooley to the region seeking justice, and when the courts failed, he began a vendetta to avenge his friend. In the ensuing months, Sheriff Clark used the mob to secure his political position by ambushing ranchers George Gladden and Moses Baird, which drew gunfighters such as John Ringo into the violence. As more men were killed, new forces joined the spiral of death. Local and state officials proved powerless, and it was not until the early 1900s that the feud burned itself out. Johnson has proven a diligent researcher in locating information concerning the Hoo Doo War. Using contemporary newspaper accounts, letters, diaries, and official reports, he analyzes the myths and legends surrounding the feud and presents the unvarnished truth of what happened in Mason County. This book is the definitive account of the Hoo Doo War, as well as a case study in frontier violence of the bloodiest kind.