The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Ethel Wedgwood | ISBN: | 9781465531964 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Ethel Wedgwood |

| ISBN: | 9781465531964 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

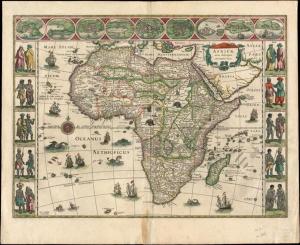

Six hundred years ago, when the histories of Europe still lay buried among the Latin Charter Rolls of great abbeys, before Piers Plowman had yet voiced the English conscience in the English tongue, and when Dante was just turning to look back on half his life’s journey, John, Lord of Joinville, full of days and honours, began to write for his liege lady his recollections of her husband’s grandfather, St. Louis. Like many Others of that line of great French memoir-writers which he heads, such, for instance, as Commines, Sully, and Marbot, Joinville was first of all a man of action, and only in the second place a man of letters; and for this very reason his book has that directness and simplicity which appeals to the common humanity of all ages. He is no skilled chronicler, like his compatriot the warrior and statesman Villehardouin; he is no born story-teller, like Villani or Froissart; but a hardheaded, plain-minded man to whom penmanship is no art, and who writes simply because he loved his friend and believes that he has a duty to his posterity. John, Lord of Joinville, was hereditary Seneschal of Champagne and head of a family already illustrious for its Crusaders. By blood and old family friendship he was closely united with the great house of Brienne, and could claim cousinship with its famous cadet, John, King of Jerusalem, father-in-law to two emperors, and himself an emperor.’ Born in 1225, Joinville was only twenty-three when he joined King Louis in the disastrous Seventh Crusade; and before he was thirty he was settled again on his estates, having escaped every conceivable peril by land and sea, to which nineteen out of every twenty men had succumbed

Six hundred years ago, when the histories of Europe still lay buried among the Latin Charter Rolls of great abbeys, before Piers Plowman had yet voiced the English conscience in the English tongue, and when Dante was just turning to look back on half his life’s journey, John, Lord of Joinville, full of days and honours, began to write for his liege lady his recollections of her husband’s grandfather, St. Louis. Like many Others of that line of great French memoir-writers which he heads, such, for instance, as Commines, Sully, and Marbot, Joinville was first of all a man of action, and only in the second place a man of letters; and for this very reason his book has that directness and simplicity which appeals to the common humanity of all ages. He is no skilled chronicler, like his compatriot the warrior and statesman Villehardouin; he is no born story-teller, like Villani or Froissart; but a hardheaded, plain-minded man to whom penmanship is no art, and who writes simply because he loved his friend and believes that he has a duty to his posterity. John, Lord of Joinville, was hereditary Seneschal of Champagne and head of a family already illustrious for its Crusaders. By blood and old family friendship he was closely united with the great house of Brienne, and could claim cousinship with its famous cadet, John, King of Jerusalem, father-in-law to two emperors, and himself an emperor.’ Born in 1225, Joinville was only twenty-three when he joined King Louis in the disastrous Seventh Crusade; and before he was thirty he was settled again on his estates, having escaped every conceivable peril by land and sea, to which nineteen out of every twenty men had succumbed