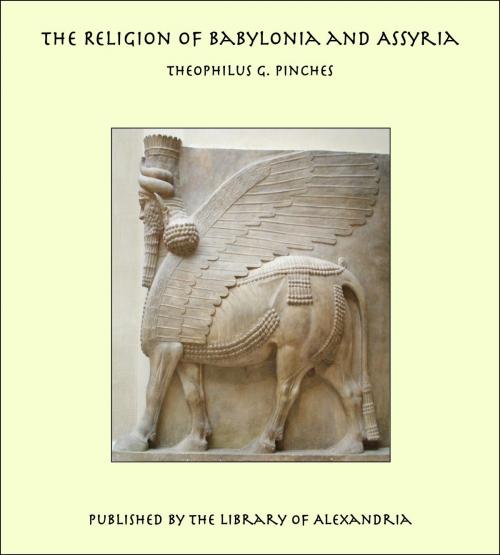

The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Theophilus G. Pinches | ISBN: | 9781465546708 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Theophilus G. Pinches |

| ISBN: | 9781465546708 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Lecturer in Assyrian at University College, London, of "The Old Testament in the Light of the Records of Assyria and Babylonia"; "The Bronze Ornaments of the Palace Gates of Balewat" etc. etc. The religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians was the polytheistic faith professed by the peoples inhabiting the Tigris and Euphrates valleys from what may be regarded as the dawn of history until the Christian era began, or, at least, until the inhabitants were brought under the influence of Christianity. The chronological period covered may be roughly estimated at about 5000 years. The belief of the people, at the end of that time, being Babylonian heathenism leavened with Judaism, the country was probably ripe for the reception of the new faith. Christianity, however, by no means replaced the earlier polytheism, as is evidenced by the fact, that the worship of Nebo and the gods associated with him continued until the fourth century of the Christian era.

It was the faith of two distinct peoples--the Sumero-Akkadians, and the Assyro-Babylonians. In what country it had its beginnings is unknown--it comes before us, even at the earliest period, as a faith already well-developed, and from that fact, as well as from the names of the numerous deities, it is clear that it began with the former race--the Sumero-Akkadians--who spoke a non-Semitic language largely affected by phonetic decay, and in which the grammatical forms had in certain cases become confused to such an extent that those who study it ask themselves whether the people who spoke it were able to understand each other without recourse to devices such as the "tones" to which the Chinese resort. With few exceptions, the names of the gods which the inscriptions reveal to us are all derived from this non-Semitic language, which furnishes us with satisfactory etymologies for such names as Merodach, Nergal, Sin, and the divinities mentioned in Berosus and Damascius, as well as those of hundreds of deities revealed to us by the tablets and slabs of Babylonia and Assyria. Outside the inscriptions of Babylonia and Assyria, there is but little bearing upon the religion of those countries, the most important fragment being the extracts from Berosus and Damascius referred to above. Among the Babylonian and Assyrian remains, however, we have an extensive and valuable mass of material, dating from the fourth or fifth millennium before Christ until the disappearance of the Babylonian system of writing about the beginning of the Christian era

It was the faith of two distinct peoples--the Sumero-Akkadians, and the Assyro-Babylonians. In what country it had its beginnings is unknown--it comes before us, even at the earliest period, as a faith already well-developed, and from that fact, as well as from the names of the numerous deities, it is clear that it began with the former race--the Sumero-Akkadians--who spoke a non-Semitic language largely affected by phonetic decay, and in which the grammatical forms had in certain cases become confused to such an extent that those who study it ask themselves whether the people who spoke it were able to understand each other without recourse to devices such as the "tones" to which the Chinese resort. With few exceptions, the names of the gods which the inscriptions reveal to us are all derived from this non-Semitic language, which furnishes us with satisfactory etymologies for such names as Merodach, Nergal, Sin, and the divinities mentioned in Berosus and Damascius, as well as those of hundreds of deities revealed to us by the tablets and slabs of Babylonia and Assyria. Outside the inscriptions of Babylonia and Assyria, there is but little bearing upon the religion of those countries, the most important fragment being the extracts from Berosus and Damascius referred to above. Among the Babylonian and Assyrian remains, however, we have an extensive and valuable mass of material, dating from the fourth or fifth millennium before Christ until the disappearance of the Babylonian system of writing about the beginning of the Christian era

Lecturer in Assyrian at University College, London, of "The Old Testament in the Light of the Records of Assyria and Babylonia"; "The Bronze Ornaments of the Palace Gates of Balewat" etc. etc. The religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians was the polytheistic faith professed by the peoples inhabiting the Tigris and Euphrates valleys from what may be regarded as the dawn of history until the Christian era began, or, at least, until the inhabitants were brought under the influence of Christianity. The chronological period covered may be roughly estimated at about 5000 years. The belief of the people, at the end of that time, being Babylonian heathenism leavened with Judaism, the country was probably ripe for the reception of the new faith. Christianity, however, by no means replaced the earlier polytheism, as is evidenced by the fact, that the worship of Nebo and the gods associated with him continued until the fourth century of the Christian era.

It was the faith of two distinct peoples--the Sumero-Akkadians, and the Assyro-Babylonians. In what country it had its beginnings is unknown--it comes before us, even at the earliest period, as a faith already well-developed, and from that fact, as well as from the names of the numerous deities, it is clear that it began with the former race--the Sumero-Akkadians--who spoke a non-Semitic language largely affected by phonetic decay, and in which the grammatical forms had in certain cases become confused to such an extent that those who study it ask themselves whether the people who spoke it were able to understand each other without recourse to devices such as the "tones" to which the Chinese resort. With few exceptions, the names of the gods which the inscriptions reveal to us are all derived from this non-Semitic language, which furnishes us with satisfactory etymologies for such names as Merodach, Nergal, Sin, and the divinities mentioned in Berosus and Damascius, as well as those of hundreds of deities revealed to us by the tablets and slabs of Babylonia and Assyria. Outside the inscriptions of Babylonia and Assyria, there is but little bearing upon the religion of those countries, the most important fragment being the extracts from Berosus and Damascius referred to above. Among the Babylonian and Assyrian remains, however, we have an extensive and valuable mass of material, dating from the fourth or fifth millennium before Christ until the disappearance of the Babylonian system of writing about the beginning of the Christian era

It was the faith of two distinct peoples--the Sumero-Akkadians, and the Assyro-Babylonians. In what country it had its beginnings is unknown--it comes before us, even at the earliest period, as a faith already well-developed, and from that fact, as well as from the names of the numerous deities, it is clear that it began with the former race--the Sumero-Akkadians--who spoke a non-Semitic language largely affected by phonetic decay, and in which the grammatical forms had in certain cases become confused to such an extent that those who study it ask themselves whether the people who spoke it were able to understand each other without recourse to devices such as the "tones" to which the Chinese resort. With few exceptions, the names of the gods which the inscriptions reveal to us are all derived from this non-Semitic language, which furnishes us with satisfactory etymologies for such names as Merodach, Nergal, Sin, and the divinities mentioned in Berosus and Damascius, as well as those of hundreds of deities revealed to us by the tablets and slabs of Babylonia and Assyria. Outside the inscriptions of Babylonia and Assyria, there is but little bearing upon the religion of those countries, the most important fragment being the extracts from Berosus and Damascius referred to above. Among the Babylonian and Assyrian remains, however, we have an extensive and valuable mass of material, dating from the fourth or fifth millennium before Christ until the disappearance of the Babylonian system of writing about the beginning of the Christian era