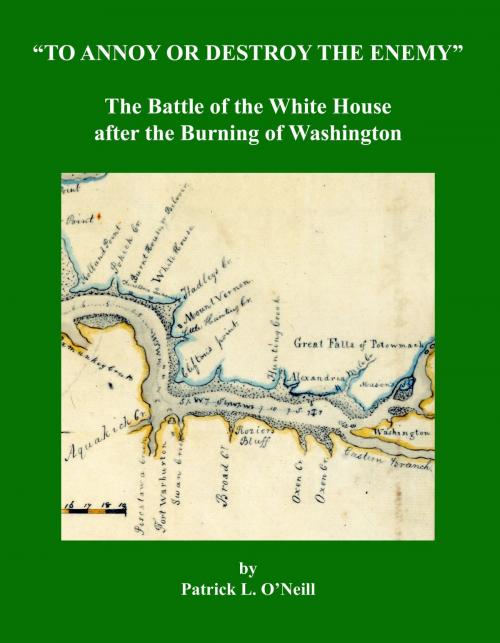

To Annoy or Destroy the Enemy

The Battle of the White House after the Burning of Washington

Nonfiction, History, Military, United States| Author: | Patrick L. O'Neill | ISBN: | 9781631920707 |

| Publisher: | BookBaby | Publication: | June 2, 2014 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Patrick L. O'Neill |

| ISBN: | 9781631920707 |

| Publisher: | BookBaby |

| Publication: | June 2, 2014 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

In the summer of 1814, it would have been difficult to imagine that seven British warships could sail up the Potomac River to the national capital city of Washington. Yet, in August 1814, two years into the War of 1812, two 36-gun frigates, three bomb vessels, a rocket ship, and a brig, all referred to as the Potomac Squadron, entered the Potomac on their way to the Washington area. As part of the plans of British Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, they were designed as a feint, assault assistance, and a retreat option for the British Army down the Potomac to their ships after the attack on Washington if the return road was blocked. Simultaneous to the squadron’s ascent, British land forces marched across southern Maryland and clashed with the Americans at Bladensburg, Maryland. After routing the Americans, the British were able to enter Washington and wreak havoc on several the Federal buildings, including the President’s mansion. The British Army left three days prior to the arrival of the squadron, who were slowed by sailing 150 miles up the difficult Potomac and encountering Virginia and Maryland militia en route. After taking Alexandria, Virginia, essentially hostage, and loading 21 prize ships of captured goods, the squadron tried to sail past defenses above a place called the White House in Virginia just south of Mount Vernon, and Indian Head Point in Maryland, in what would become known as the Battle of the White House and Battle of Indian Head, respectively. This White House was not the President’s Mansion burned the week earlier in Washington, but an old customs house on the Potomac just south of Mount Vernon on Belvoir Neck. The setting was the site of a five day battle that helped change the course of the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake Bay and has been largely overlooked by history. In what became one of the longest battles of the war, British and American forces engaged from September 1-5, 1814, in the first American offense caused by the burning of Washington. The battle involved 2500-3000 Virginia, Maryland and District of Columbia militia, over 500 American Navy seamen, three American naval legends, the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of State (and Acting Secretary of War), an internationally known inventor, seven British warships, and several hundred seasoned British seamen and marines. The American attack on the Potomac Squadron caused the entire British fleet in the Chesapeake to change their course. The attack also played a significant role in compelling the British to attack Baltimore more than seven weeks earlier than Vice Admiral Cochrane’s intended target date, which ultimately led to the British defeat. Two hundred years have passed since the Potomac Squadron fought their way past the White House batteries, eclipsed by the burning of Washington and the bombarding of Fort McHenry. This book will reveal what history has forgotten; about America’s first response to the attack on the nation’s capital and the events that truly led to the penning of the Star Spangled Banner in what British naval historian William James wrote in 1837: Of the many expeditions up the bays and rivers of the United States during the late war, none equaled in brilliancy of execution that of the Potomac to Alexandria.

In the summer of 1814, it would have been difficult to imagine that seven British warships could sail up the Potomac River to the national capital city of Washington. Yet, in August 1814, two years into the War of 1812, two 36-gun frigates, three bomb vessels, a rocket ship, and a brig, all referred to as the Potomac Squadron, entered the Potomac on their way to the Washington area. As part of the plans of British Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, they were designed as a feint, assault assistance, and a retreat option for the British Army down the Potomac to their ships after the attack on Washington if the return road was blocked. Simultaneous to the squadron’s ascent, British land forces marched across southern Maryland and clashed with the Americans at Bladensburg, Maryland. After routing the Americans, the British were able to enter Washington and wreak havoc on several the Federal buildings, including the President’s mansion. The British Army left three days prior to the arrival of the squadron, who were slowed by sailing 150 miles up the difficult Potomac and encountering Virginia and Maryland militia en route. After taking Alexandria, Virginia, essentially hostage, and loading 21 prize ships of captured goods, the squadron tried to sail past defenses above a place called the White House in Virginia just south of Mount Vernon, and Indian Head Point in Maryland, in what would become known as the Battle of the White House and Battle of Indian Head, respectively. This White House was not the President’s Mansion burned the week earlier in Washington, but an old customs house on the Potomac just south of Mount Vernon on Belvoir Neck. The setting was the site of a five day battle that helped change the course of the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake Bay and has been largely overlooked by history. In what became one of the longest battles of the war, British and American forces engaged from September 1-5, 1814, in the first American offense caused by the burning of Washington. The battle involved 2500-3000 Virginia, Maryland and District of Columbia militia, over 500 American Navy seamen, three American naval legends, the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of State (and Acting Secretary of War), an internationally known inventor, seven British warships, and several hundred seasoned British seamen and marines. The American attack on the Potomac Squadron caused the entire British fleet in the Chesapeake to change their course. The attack also played a significant role in compelling the British to attack Baltimore more than seven weeks earlier than Vice Admiral Cochrane’s intended target date, which ultimately led to the British defeat. Two hundred years have passed since the Potomac Squadron fought their way past the White House batteries, eclipsed by the burning of Washington and the bombarding of Fort McHenry. This book will reveal what history has forgotten; about America’s first response to the attack on the nation’s capital and the events that truly led to the penning of the Star Spangled Banner in what British naval historian William James wrote in 1837: Of the many expeditions up the bays and rivers of the United States during the late war, none equaled in brilliancy of execution that of the Potomac to Alexandria.