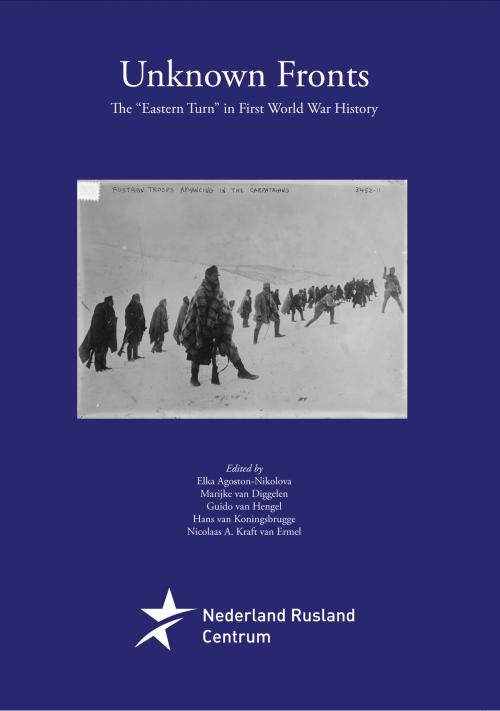

Unknown Fronts

The "Eastern Turn" in First World War History

Nonfiction, History, Eastern Europe, Military, World War I, Modern, 20th Century| Author: | Elka Agoston-Nikolova, Marijke van Diggelen, Guido van Hengel, Hans van Koningsbrugge, Nicolaas A. Kraft van Ermel | ISBN: | 9789082559019 |

| Publisher: | Netherlands-Russia Centre | Publication: | February 1, 2017 |

| Imprint: | I | Language: | English |

| Author: | Elka Agoston-Nikolova, Marijke van Diggelen, Guido van Hengel, Hans van Koningsbrugge, Nicolaas A. Kraft van Ermel |

| ISBN: | 9789082559019 |

| Publisher: | Netherlands-Russia Centre |

| Publication: | February 1, 2017 |

| Imprint: | I |

| Language: | English |

One hundred years ago Europe unleashed a storm of violence upon the world: The First World War had an enormous impact on the lives of Europeans, European history and culture. To this day, the iconic images of trench warfare in Belgium and France are burned onto our retinas, the names of its major battles, such as The Somme, Verdun and Ypres, are etched in our consciousness, as are the stories of modern warfare’s greatest horrors: the usage of poison gas and new technical means such as aerial warfare and the tank.

In recent years it has become clear that this is only a small part of the Great War’s history. In many senses there were other fronts: both geographically, as well as thematically the war was fought on fronts that have remained relatively ‘unknown’ to date. From a geographical perspective there were many other fronts on the European continent alone, there was fighting in the Balkans, in Romania and in the borderlands of the German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires (an area that is today part of Poland, Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic States). Outside of Europe there was also warfare in European colonies in Africa and in the Middle East. Seen from a thematic angle, these ‘unknown fronts’ relate to the life and conduct of civilians and diplomats who lived and worked in the war. Civilians might serve as (para)medical professionals or might have fallen victim to one of the war’s many violent episodes. Diplomats might have served the interests of their countries of origin in one of the many belligerents, yet, their documents can also shed light on different aspects of the war. Then there are soldiers themselves, whose voices have not always been heard. Yet another unknown front, is the life and work of intellectuals, who did not partake in violent actions, but often took up the weapon of the pen to wage their war.

Since the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Iron Curtain, many aspects of the Eastern fronts of the First World War have come to light and new sources have been uncovered. So to speak, there has been an ‘Eastern turn’ in First World War historiography. The scholars who contributed to this volume, all historians or literary scholars, have researched new sources on those Eastern fronts and have given new valuable insights in several ‘unknown fronts’ of the Great War, but also had to conclude that there are still many unanswered questions that need further inquiry. A revision of historiographical insights on the First World War is however warranted.

One hundred years ago Europe unleashed a storm of violence upon the world: The First World War had an enormous impact on the lives of Europeans, European history and culture. To this day, the iconic images of trench warfare in Belgium and France are burned onto our retinas, the names of its major battles, such as The Somme, Verdun and Ypres, are etched in our consciousness, as are the stories of modern warfare’s greatest horrors: the usage of poison gas and new technical means such as aerial warfare and the tank.

In recent years it has become clear that this is only a small part of the Great War’s history. In many senses there were other fronts: both geographically, as well as thematically the war was fought on fronts that have remained relatively ‘unknown’ to date. From a geographical perspective there were many other fronts on the European continent alone, there was fighting in the Balkans, in Romania and in the borderlands of the German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires (an area that is today part of Poland, Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic States). Outside of Europe there was also warfare in European colonies in Africa and in the Middle East. Seen from a thematic angle, these ‘unknown fronts’ relate to the life and conduct of civilians and diplomats who lived and worked in the war. Civilians might serve as (para)medical professionals or might have fallen victim to one of the war’s many violent episodes. Diplomats might have served the interests of their countries of origin in one of the many belligerents, yet, their documents can also shed light on different aspects of the war. Then there are soldiers themselves, whose voices have not always been heard. Yet another unknown front, is the life and work of intellectuals, who did not partake in violent actions, but often took up the weapon of the pen to wage their war.

Since the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Iron Curtain, many aspects of the Eastern fronts of the First World War have come to light and new sources have been uncovered. So to speak, there has been an ‘Eastern turn’ in First World War historiography. The scholars who contributed to this volume, all historians or literary scholars, have researched new sources on those Eastern fronts and have given new valuable insights in several ‘unknown fronts’ of the Great War, but also had to conclude that there are still many unanswered questions that need further inquiry. A revision of historiographical insights on the First World War is however warranted.