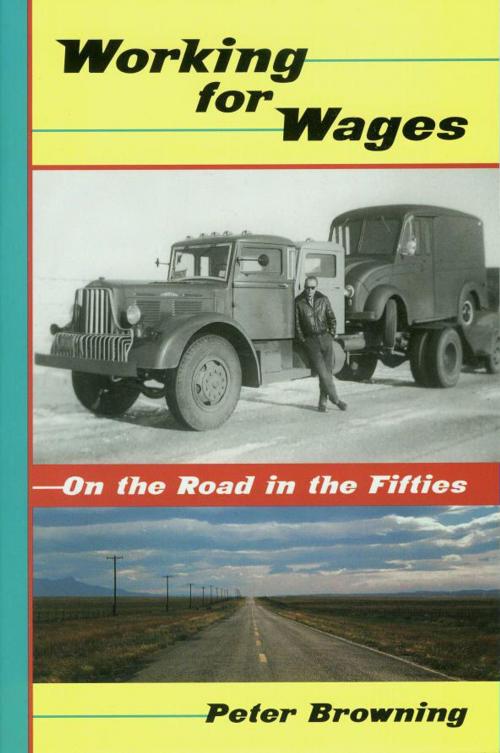

| Author: | Peter Browning | ISBN: | 9780944220351 |

| Publisher: | Great West Books | Publication: | February 18, 2013 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Peter Browning |

| ISBN: | 9780944220351 |

| Publisher: | Great West Books |

| Publication: | February 18, 2013 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

I was born in Cleveland, Ohio on the last day of 1928. Both my parents were college graduates, my upbringing—and values and standards —were upper-middle class, and in the normal course of events I would have acquired a “higher education” and quite likely proceeded into one of the professions.

I made a couple of stabs at college, but dropped out both times after a few weeks. I had several dull jobs, and then—in the young man’s tradition of perversity—I did what was most inimical to my own interests: I joined the Navy.

The Navy was dead time—a period of going through the motions while waiting to get out. Once I was free again I reentered college, sat through one class, and dropped out while I was still ahead. I hadn’t the least idea of what I might do in life—or with my life—and the urge to travel was my primary motivation.

After an eight-week stint as a deckhand on an iron-ore carrier on the Great Lakes, I signed on with the “Old Man” to make a one-way trip from Detroit to Los Angeles, with no notion of what I would do when I got to the Coast—and I wound up driving for the Old Man for nine and a half years. My companions on the job were not the sort of people I had known before. They thought and acted differently, and had different expectations and prospects in life. What we had in common were travel fever, no plans for the future, and no homes. The real home was the job—constant motion and a succession of hotel rooms. The future was the next trip. The knowledge that there would be several trips in a row constituted our version of stability and permanence.

I was on the road for the Old Man from May 1949 to December 1958, and during that period drove new cars and trucks from Detroit to Los Angeles 130 times. When I started, the country was still recovering from the Great Depression and the Second World War. Nine and a half years later, millions of people had realized their onward-and-upward aspirations: a new car, a house in the suburbs, a good job, money in the bank—and the kids had braces on their teethThe world passed us by. The end of the fifties saw us no better off than at the beginning. There was motion without progress, and nothing to show for our labors. We were older and tireder, wiser and more cynical. I acquired some of the outlook of my companions while retaining my own, and gained an education of the sort that cannot be taught but must be learned.

What follows is an anecdotal account of who we were, how we lived, and how we talked. None of these tales is precisely true in every respect, yet none is false. Most of the names have been changed to protect the innocent and the guilty alike.

When the Old Man folded up his tent we were left stranded, but we were not without resources. Our instincts, our experience, our habits, the very history of the country showed us the way. We went west once more, to start life anew.

I was born in Cleveland, Ohio on the last day of 1928. Both my parents were college graduates, my upbringing—and values and standards —were upper-middle class, and in the normal course of events I would have acquired a “higher education” and quite likely proceeded into one of the professions.

I made a couple of stabs at college, but dropped out both times after a few weeks. I had several dull jobs, and then—in the young man’s tradition of perversity—I did what was most inimical to my own interests: I joined the Navy.

The Navy was dead time—a period of going through the motions while waiting to get out. Once I was free again I reentered college, sat through one class, and dropped out while I was still ahead. I hadn’t the least idea of what I might do in life—or with my life—and the urge to travel was my primary motivation.

After an eight-week stint as a deckhand on an iron-ore carrier on the Great Lakes, I signed on with the “Old Man” to make a one-way trip from Detroit to Los Angeles, with no notion of what I would do when I got to the Coast—and I wound up driving for the Old Man for nine and a half years. My companions on the job were not the sort of people I had known before. They thought and acted differently, and had different expectations and prospects in life. What we had in common were travel fever, no plans for the future, and no homes. The real home was the job—constant motion and a succession of hotel rooms. The future was the next trip. The knowledge that there would be several trips in a row constituted our version of stability and permanence.

I was on the road for the Old Man from May 1949 to December 1958, and during that period drove new cars and trucks from Detroit to Los Angeles 130 times. When I started, the country was still recovering from the Great Depression and the Second World War. Nine and a half years later, millions of people had realized their onward-and-upward aspirations: a new car, a house in the suburbs, a good job, money in the bank—and the kids had braces on their teethThe world passed us by. The end of the fifties saw us no better off than at the beginning. There was motion without progress, and nothing to show for our labors. We were older and tireder, wiser and more cynical. I acquired some of the outlook of my companions while retaining my own, and gained an education of the sort that cannot be taught but must be learned.

What follows is an anecdotal account of who we were, how we lived, and how we talked. None of these tales is precisely true in every respect, yet none is false. Most of the names have been changed to protect the innocent and the guilty alike.

When the Old Man folded up his tent we were left stranded, but we were not without resources. Our instincts, our experience, our habits, the very history of the country showed us the way. We went west once more, to start life anew.