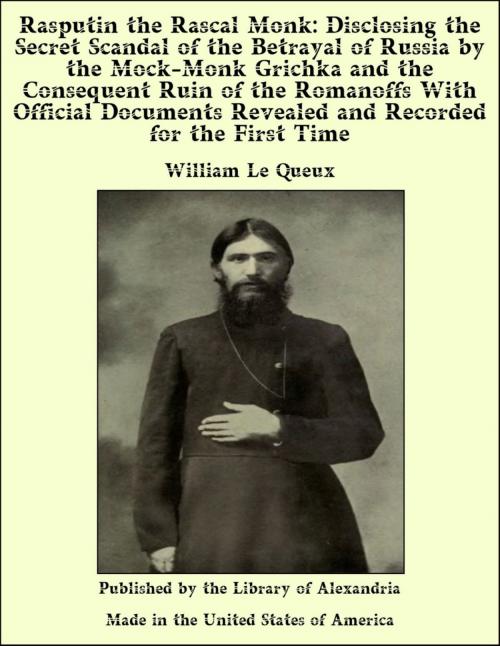

Rasputin the Rascal Monk: Disclosing the Secret Scandal of the Betrayal of Russia by the Mock-Monk Grichka and the Consequent Ruin of the Romanoffs With Official Documents Revealed and Recorded for the First Time

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | William Le Queux | ISBN: | 9781465595485 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | William Le Queux |

| ISBN: | 9781465595485 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

The war has revealed many strange personalities in Europe, but surely none so sinister or so remarkable as that of the mock-monk Gregory Novikh—the middle-aged, uncleanly charlatan, now happily dead, whom Russia knew as Rasputin. As one whose duty it was before the war to travel extensively backwards and forwards across the face of Europe, in order to make explorations into the underworld of the politics of those who might be our friends—or enemies as Fate might decide—I heard much of the drunken, dissolute scoundrel from Siberia who, beneath the cloak of religion and asceticism, was attracting a host of silly, neurotic women because he had invented a variation of the many new religions known through all the ages from the days of Rameses the Great. On one occasion, three years before the world-crisis, I found myself at the obscure little fishing-village called Alexandrovsk, on the Arctic shore, a grey rock-bound place into which the black chill waves sweep with great violence and where, for four months in the year, it is perpetual night. To-day, Alexandrovsk is a port connected with Petrograd by railway, bad though it be, which passes over the great marshy tundra, and in consequence has been of greatest importance to Russia since the war. While inspecting the quays which had then just been commenced, my friend Volkhovski, the Russian engineer, introduced me to an unkempt disreputable-looking “pope” with remarkable steel-grey eyes, whose appearance was distinctly uncleanly, and whom I dismissed with a few polite words. “That is Grichka (pronounced Greesh-ka), the miracle-worker!” my friend explained after he had ambled away. “He is one of the very few who has access to the Tsar at any hour.” “Why?” I asked, instantly interested in the mysterious person whose very name the Russian Censor would never allow to be even mentioned in the newspapers. My friend shrugged his broad shoulders and grinned. “Many strange stories are told of him in Moscow and in Petrograd,” he said. “No doubt you have heard of his curious new religion, of his dozen wives of noble birth who live together far away in Pokrovsky!”

The war has revealed many strange personalities in Europe, but surely none so sinister or so remarkable as that of the mock-monk Gregory Novikh—the middle-aged, uncleanly charlatan, now happily dead, whom Russia knew as Rasputin. As one whose duty it was before the war to travel extensively backwards and forwards across the face of Europe, in order to make explorations into the underworld of the politics of those who might be our friends—or enemies as Fate might decide—I heard much of the drunken, dissolute scoundrel from Siberia who, beneath the cloak of religion and asceticism, was attracting a host of silly, neurotic women because he had invented a variation of the many new religions known through all the ages from the days of Rameses the Great. On one occasion, three years before the world-crisis, I found myself at the obscure little fishing-village called Alexandrovsk, on the Arctic shore, a grey rock-bound place into which the black chill waves sweep with great violence and where, for four months in the year, it is perpetual night. To-day, Alexandrovsk is a port connected with Petrograd by railway, bad though it be, which passes over the great marshy tundra, and in consequence has been of greatest importance to Russia since the war. While inspecting the quays which had then just been commenced, my friend Volkhovski, the Russian engineer, introduced me to an unkempt disreputable-looking “pope” with remarkable steel-grey eyes, whose appearance was distinctly uncleanly, and whom I dismissed with a few polite words. “That is Grichka (pronounced Greesh-ka), the miracle-worker!” my friend explained after he had ambled away. “He is one of the very few who has access to the Tsar at any hour.” “Why?” I asked, instantly interested in the mysterious person whose very name the Russian Censor would never allow to be even mentioned in the newspapers. My friend shrugged his broad shoulders and grinned. “Many strange stories are told of him in Moscow and in Petrograd,” he said. “No doubt you have heard of his curious new religion, of his dozen wives of noble birth who live together far away in Pokrovsky!”