| Author: | Dante Alighieri | ISBN: | 9780599456426 |

| Publisher: | Lighthouse Books for Translation Publishing | Publication: | May 10, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Lighthouse Books for Translation and Publishing | Language: | English |

| Author: | Dante Alighieri |

| ISBN: | 9780599456426 |

| Publisher: | Lighthouse Books for Translation Publishing |

| Publication: | May 10, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Lighthouse Books for Translation and Publishing |

| Language: | English |

La Vita Nuova or Vita Nova is a text by Dante Alighieri published in 1295. It is an expression of the medieval genre of courtly love in a prosimetrum style, a combination of both prose and verse.

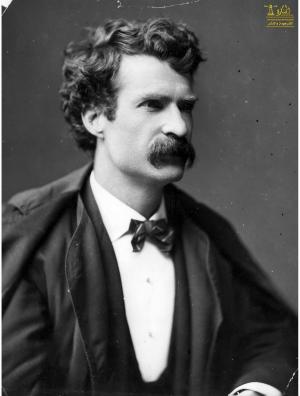

Dante, in full Dante Alighieri, (born c. May 21–June 20, 1265, Florence, Italy—died September 13/14, 1321, Ravenna), Italian poet, prose writer, literary theorist, moral philosopher, and political thinker. He is best known for the monumental epic poem La commedia, later named La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy).

Dante’s Divine Comedy, a landmark in Italian literature and among the greatest works of all medieval European literature, is a profound Christian vision of humankind’s temporal and eternal destiny. On its most personal level, it draws on Dante’s own experience of exile from his native city of Florence. On its most comprehensive level, it may be read as an allegory, taking the form of a journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise. The poem amazes by its array of learning, its penetrating and comprehensive analysis of contemporary problems, and its inventiveness of language and imagery. By choosing to write his poem in the Italian vernacular rather than in Latin, Dante decisively influenced the course of literary development. (He primarily used the Tuscan dialect, which would become standard literary Italian, but his vivid vocabulary ranged widely over many dialects and languages.) Not only did he lend a voice to the emerging lay culture of his own country, but Italian became the literary language in western Europe for several centuries.

In addition to poetry Dante wrote important theoretical works ranging from discussions of rhetoric to moral philosophy and political thought. He was fully conversant with the classical tradition, drawing for his own purposes on such writers as Virgil, Cicero, and Boethius. But, most unusual for a layman, he also had an impressive command of the most recent scholastic philosophy and of theology. His learning and his personal involvement in the heated political controversies of his age led him to the composition of De monarchia, one of the major tracts of medieval political philosophy.

Most of what is known about Dante’s life he has told himself. He was born in Florence in 1265 under the sign of Gemini (between May 21 and June 20) and remained devoted to his native city all his life. Dante describes how he fought as a cavalryman against the Ghibellines, a banished Florentine party supporting the imperial cause. He also speaks of his great teacher Brunetto Latini and his gifted friend Guido Cavalcanti, of the poetic culture in which he made his first artistic ventures, his poetic indebtedness to Guido Guinizelli, the origins of his family in his great-great-grandfather, Cacciaguida, whom the reader meets in the central cantos of the Paradiso (and from whose wife the family name, Alighieri, derived), and, going back even further, of the pride that he felt in the fact that his distant ancestors were descendants of the Roman soldiers who settled along the banks of the Arno.

La Vita Nuova or Vita Nova is a text by Dante Alighieri published in 1295. It is an expression of the medieval genre of courtly love in a prosimetrum style, a combination of both prose and verse.

Dante, in full Dante Alighieri, (born c. May 21–June 20, 1265, Florence, Italy—died September 13/14, 1321, Ravenna), Italian poet, prose writer, literary theorist, moral philosopher, and political thinker. He is best known for the monumental epic poem La commedia, later named La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy).

Dante’s Divine Comedy, a landmark in Italian literature and among the greatest works of all medieval European literature, is a profound Christian vision of humankind’s temporal and eternal destiny. On its most personal level, it draws on Dante’s own experience of exile from his native city of Florence. On its most comprehensive level, it may be read as an allegory, taking the form of a journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise. The poem amazes by its array of learning, its penetrating and comprehensive analysis of contemporary problems, and its inventiveness of language and imagery. By choosing to write his poem in the Italian vernacular rather than in Latin, Dante decisively influenced the course of literary development. (He primarily used the Tuscan dialect, which would become standard literary Italian, but his vivid vocabulary ranged widely over many dialects and languages.) Not only did he lend a voice to the emerging lay culture of his own country, but Italian became the literary language in western Europe for several centuries.

In addition to poetry Dante wrote important theoretical works ranging from discussions of rhetoric to moral philosophy and political thought. He was fully conversant with the classical tradition, drawing for his own purposes on such writers as Virgil, Cicero, and Boethius. But, most unusual for a layman, he also had an impressive command of the most recent scholastic philosophy and of theology. His learning and his personal involvement in the heated political controversies of his age led him to the composition of De monarchia, one of the major tracts of medieval political philosophy.

Most of what is known about Dante’s life he has told himself. He was born in Florence in 1265 under the sign of Gemini (between May 21 and June 20) and remained devoted to his native city all his life. Dante describes how he fought as a cavalryman against the Ghibellines, a banished Florentine party supporting the imperial cause. He also speaks of his great teacher Brunetto Latini and his gifted friend Guido Cavalcanti, of the poetic culture in which he made his first artistic ventures, his poetic indebtedness to Guido Guinizelli, the origins of his family in his great-great-grandfather, Cacciaguida, whom the reader meets in the central cantos of the Paradiso (and from whose wife the family name, Alighieri, derived), and, going back even further, of the pride that he felt in the fact that his distant ancestors were descendants of the Roman soldiers who settled along the banks of the Arno.