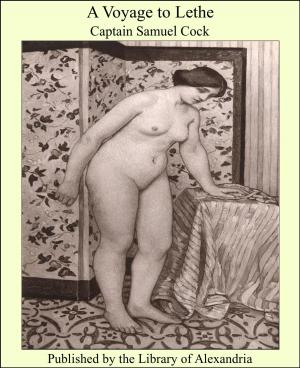

Woman Triumphant: (La Maja Desnuda)

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Vicente Blasco Ibáñez | ISBN: | 9781465534798 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Vicente Blasco Ibáñez |

| ISBN: | 9781465534798 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

The title of this novel in the original, La maja desnuda, "The Nude Maja," is also the name of one of the most famous pictures of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya. The word maja has no exact equivalent in English or in any of the modern languages. Literally, it means "bedecked," "showy," "gaudily attired," "flashy," "dazzling," etc., and it was applied at the end of the eighteenth century and at the beginning of the nineteenth to a certain class of gay women of the lower strata of Madrid society notorious for their love of dancing and their fondness for exhibiting themselves conspicuously at bull-fights and all popular celebrations. The great ladies of the aristocracy affected the free ways and imitated the picturesque dress of the maja; Goya made this type the central figure of many of his genre paintings, and the dramatist Ramón de la Cruz based most of his sainetes—farcical pieces in one act—upon the customs and rivalries of these women. The dress invented by the maja, consisting of a short skirt partly covered by a net with berry-shaped tassels, white mantilla and high shell-comb, is considered all over the world as the national costume of Spanish women. When the novel first appeared in Spain some years ago, a certain part of the Madrid public, unduly evil-minded, thought that it had discovered the identity of the real persons whom I had taken as models to draw my characters. This claim provoked a scandalous sensation and gave my book an unwholesome notoriety. It was thought that the protagonists of La maja desnuda were an illustrious Spanish painter of world-wide fame, who is my friend, and an aristocratic lady very celebrated at the time but now forgotten. I protested against this unwarranted and fantastic interpretation. Although I draw my characters from life, I do so only in a very fragmentary way (like all the great creative novelists whom I admire as masters in the field of fiction), using the materials gathered in my observations to form completely new types which are the direct and legitimate offspring of my own imagination. To use a figure: as a novelist I am a painter, not a photographer. Although I seek my inspiration in reality, I copy it in accordance with my own way of seeing it; I do not reproduce it with the mechanical servility of the photographic camera. It is possible that my imaginary heroes are vaguely reminiscent of beings who actually exist. Subconsciousness is the novelist's principal instrument, and this subconsciousness frequently mocks us, leading us to mistake for our own creation the things which we have unwittingly observed in Nature. But despite this, it is unfair, as well as risky, for the reader to assign the names of real persons to the characters of fiction, saying, "This is So-and-so

The title of this novel in the original, La maja desnuda, "The Nude Maja," is also the name of one of the most famous pictures of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya. The word maja has no exact equivalent in English or in any of the modern languages. Literally, it means "bedecked," "showy," "gaudily attired," "flashy," "dazzling," etc., and it was applied at the end of the eighteenth century and at the beginning of the nineteenth to a certain class of gay women of the lower strata of Madrid society notorious for their love of dancing and their fondness for exhibiting themselves conspicuously at bull-fights and all popular celebrations. The great ladies of the aristocracy affected the free ways and imitated the picturesque dress of the maja; Goya made this type the central figure of many of his genre paintings, and the dramatist Ramón de la Cruz based most of his sainetes—farcical pieces in one act—upon the customs and rivalries of these women. The dress invented by the maja, consisting of a short skirt partly covered by a net with berry-shaped tassels, white mantilla and high shell-comb, is considered all over the world as the national costume of Spanish women. When the novel first appeared in Spain some years ago, a certain part of the Madrid public, unduly evil-minded, thought that it had discovered the identity of the real persons whom I had taken as models to draw my characters. This claim provoked a scandalous sensation and gave my book an unwholesome notoriety. It was thought that the protagonists of La maja desnuda were an illustrious Spanish painter of world-wide fame, who is my friend, and an aristocratic lady very celebrated at the time but now forgotten. I protested against this unwarranted and fantastic interpretation. Although I draw my characters from life, I do so only in a very fragmentary way (like all the great creative novelists whom I admire as masters in the field of fiction), using the materials gathered in my observations to form completely new types which are the direct and legitimate offspring of my own imagination. To use a figure: as a novelist I am a painter, not a photographer. Although I seek my inspiration in reality, I copy it in accordance with my own way of seeing it; I do not reproduce it with the mechanical servility of the photographic camera. It is possible that my imaginary heroes are vaguely reminiscent of beings who actually exist. Subconsciousness is the novelist's principal instrument, and this subconsciousness frequently mocks us, leading us to mistake for our own creation the things which we have unwittingly observed in Nature. But despite this, it is unfair, as well as risky, for the reader to assign the names of real persons to the characters of fiction, saying, "This is So-and-so